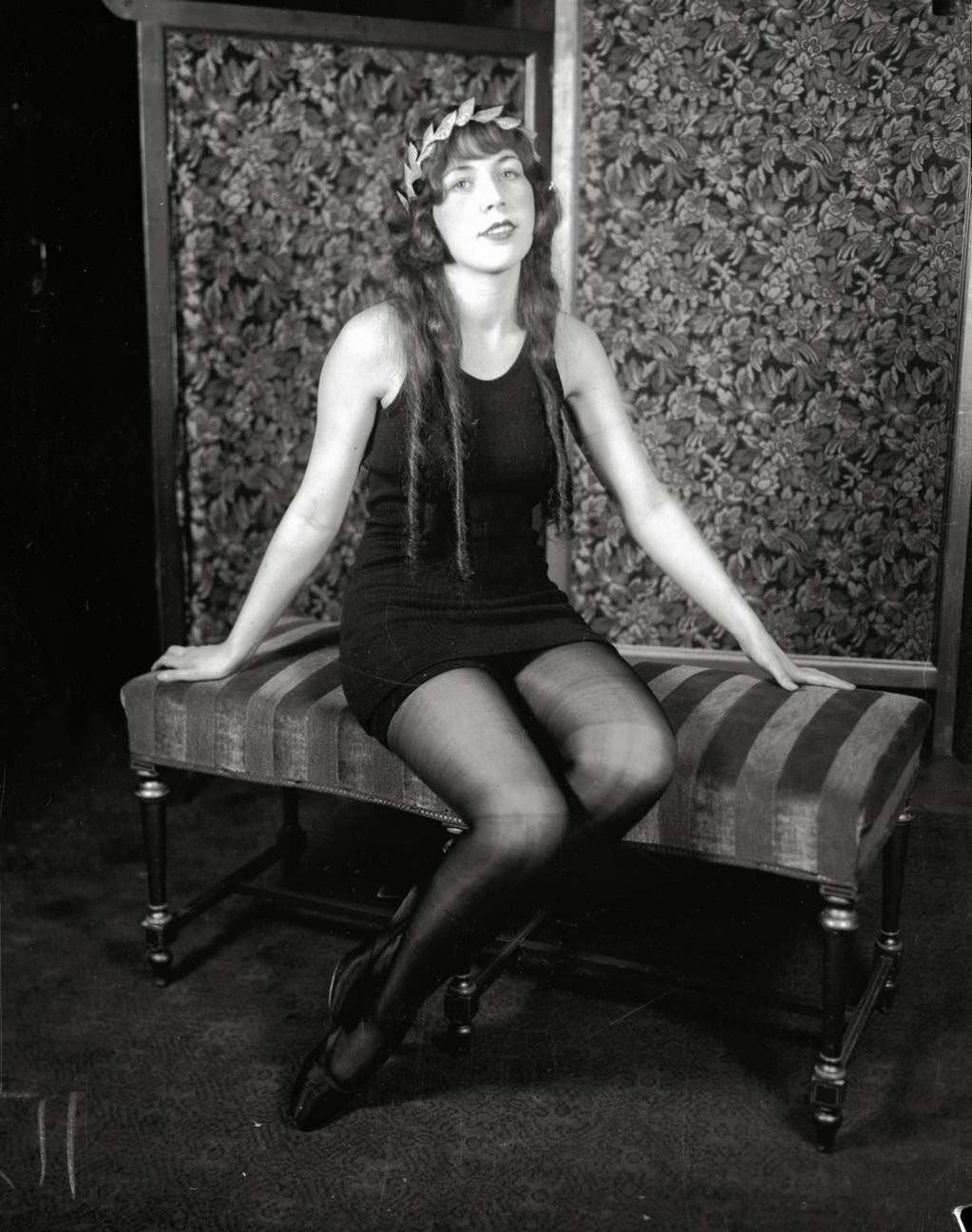

In the early 1920s, Chicago became a center for beauty contests and the rise of a new type of public female image. As the flapper style gained attention across the country, young women in Chicago embraced bold changes in fashion, attitude, and public life. These women were not just following trends—they were becoming symbols of modern culture.

The Miss Chicago contest began in 1922. It was part of a growing movement of city-wide beauty pageants across the United States. Just one year earlier, the Miss America contest had started in Atlantic City. Chicago wasted no time joining the trend. Young women in the city lined up for a chance to be crowned. The contest involved swimwear, stage walks, and interviews, but it was also about public excitement. Crowds gathered to see the newest style of beauty, one that reflected the freedom and energy of the time.

Contestants wore short bobbed hair, lined their eyes with dark makeup, and smiled with confidence. The dresses were shorter, the colors were brighter, and the girls stood with pride. Most of the competitors were working-class women. They came from neighborhoods across the city, from Bridgeport to Uptown. Many worked in department stores, factories, or offices, and they saw the contest as a way to earn respect and attention.

Read more

Chicago’s beaches along Lake Michigan provided a perfect stage for the early rounds of the competition. Bathing suits were an essential part of the event. In the 1920s, one-piece swimsuits were considered daring. But they became the standard for contests like Miss Chicago. The designs hugged the waist, exposed the legs, and allowed freedom of movement.

Newspapers across the city covered every stage of the contest. The Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Daily News published photographs of the winners. Captions described their hometowns, their hobbies, and their plans for the future. One contestant, Lillian Anderson, worked as a switchboard operator before entering the contest. She made the front page after winning the semi-finals held on Navy Pier.

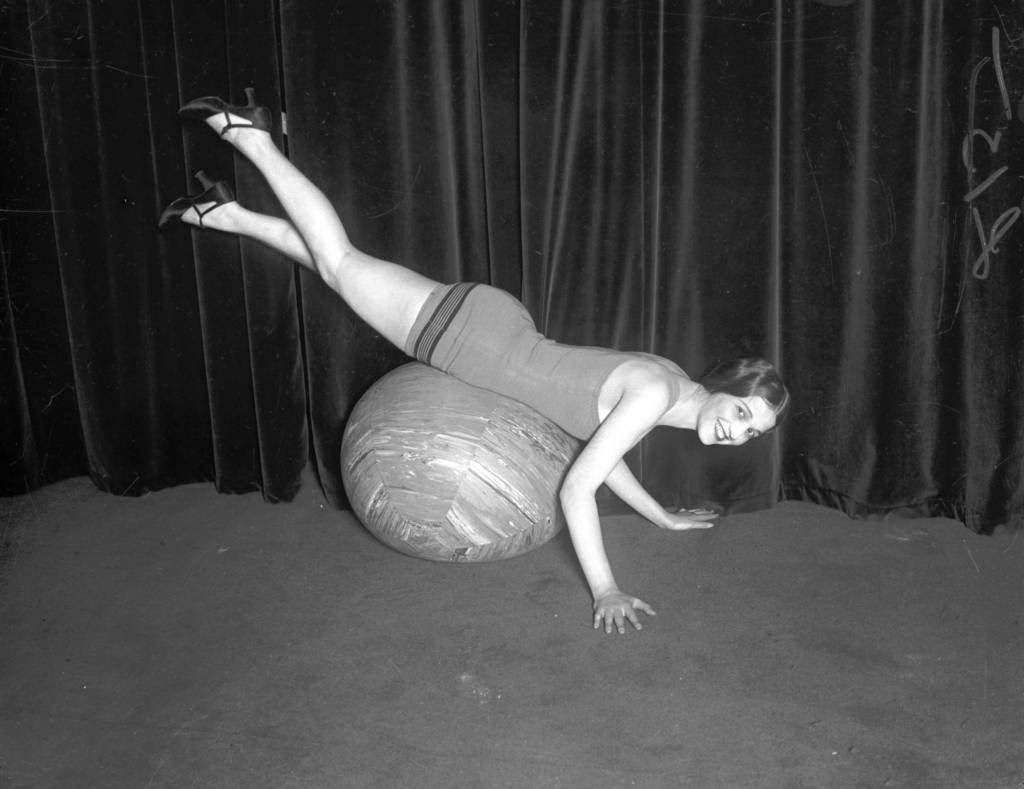

The contests were not limited to one season. Summer brought beach competitions, but winter versions were held indoors. Some were staged at hotel ballrooms or local theaters. In these events, women wore evening dresses and performed short speeches or dances. They were judged not only on their looks but also on their stage presence.

Photographers, including staff from LIFE and Chicago Daily News, captured the details. Black-and-white images show rows of young women standing side by side, smiling into the camera. Some wave, others pose with hands on hips. In several images, large crowds stand behind ropes, watching closely.

The contestants came from diverse backgrounds. Some were daughters of immigrants, others born into long-standing Chicago families. Their shared goal was visibility. In a decade marked by jazz, Prohibition, and social change, being a “bathing beauty” in Chicago meant being seen.

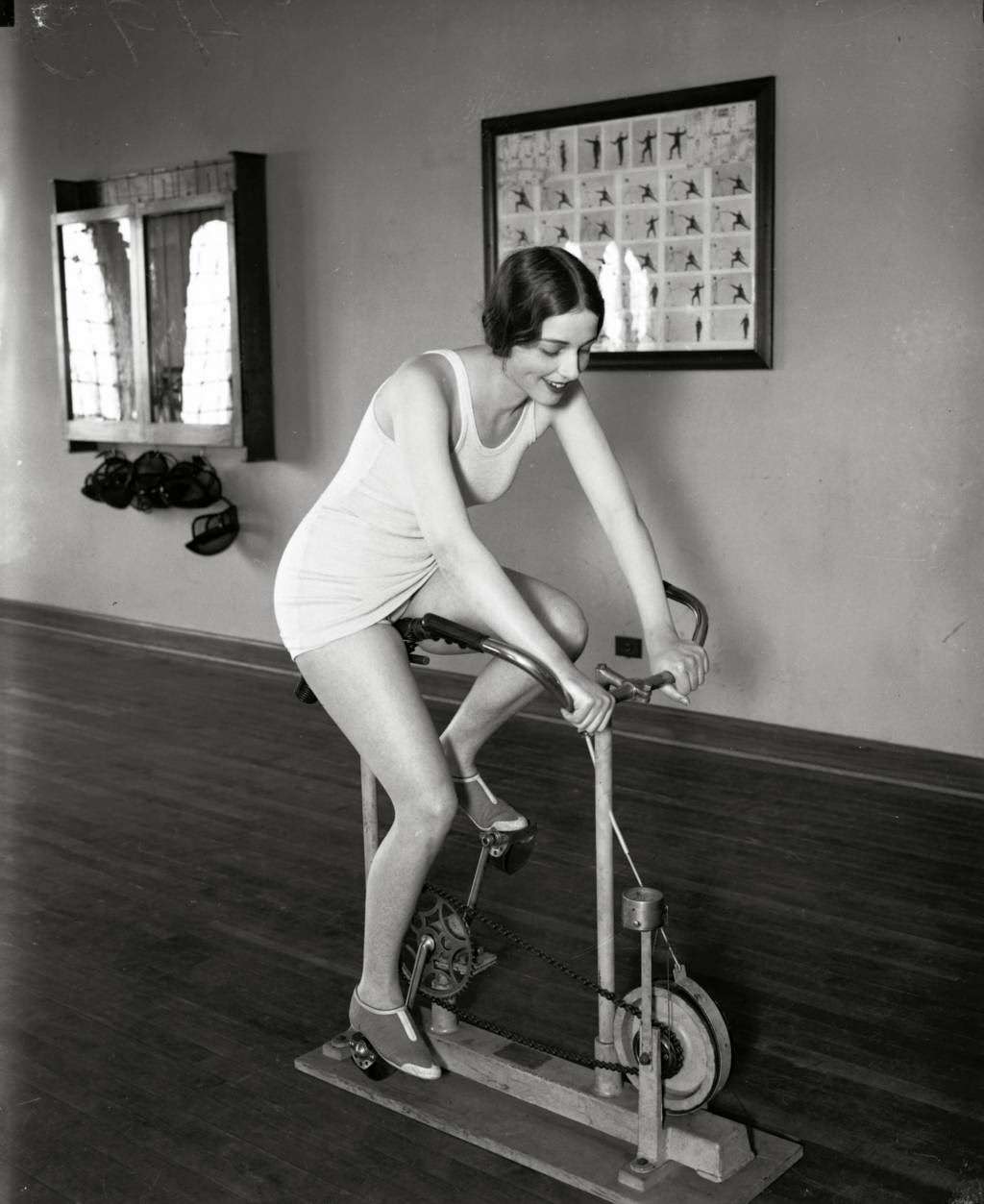

Many winners were invited to join parades, perform in vaudeville shows, or appear in store ads. Marshall Field’s, one of Chicago’s major department stores, regularly hired contestants to model clothing for its catalogs and window displays. One 1925 Miss Chicago runner-up later appeared in an ad for a new line of hosiery, her face printed across thousands of newspapers.

Behind the scenes, local businessmen sponsored the events. Theater owners, clothing brands, and even radio stations wanted their names tied to the contest. Winners often received gift certificates, travel packages, or clothing. In some cases, the prizes included contracts to appear in traveling theater shows across the Midwest.

Although most contestants returned to daily life after the event, a few found long-term careers in entertainment. One notable example was Dorothy Harris, who won a major title in 1927. She soon moved to Los Angeles and landed small film roles in silent movies. Her success drew national attention back to Chicago’s contest and increased its popularity.

The 1920s were a time of fast change, and the Miss Chicago contest captured that energy. Women were stepping into the public eye in new ways. The city’s media and businesses supported the contests, knowing they were tapping into a strong cultural wave.