The making of Gone with the Wind was an extraordinary endeavor that pushed the boundaries of 1930s filmmaking. Released in 1939, this epic film was directed by Victor Fleming and produced by David O. Selznick. Based on Margaret Mitchell’s best-selling novel, the movie’s production was as dramatic and challenging as the story it portrayed. From casting controversies to technical innovations, the creation of Gone with the Wind was a monumental task that demanded the utmost dedication from everyone involved.

Pre-Production and Casting Challenges

David O. Selznick acquired the rights to Margaret Mitchell’s novel in 1936, shortly after its publication. It became an immediate sensation, sparking immense interest in a film adaptation. Selznick paid a then-record $50,000 for the rights, a decision that demonstrated his confidence in the story’s potential. However, turning the novel into a screenplay was no small feat. Sidney Howard, the screenwriter, faced the daunting task of condensing a sprawling, 1,000-page novel into a coherent script. The script underwent numerous revisions and additions from other writers, including Selznick himself.

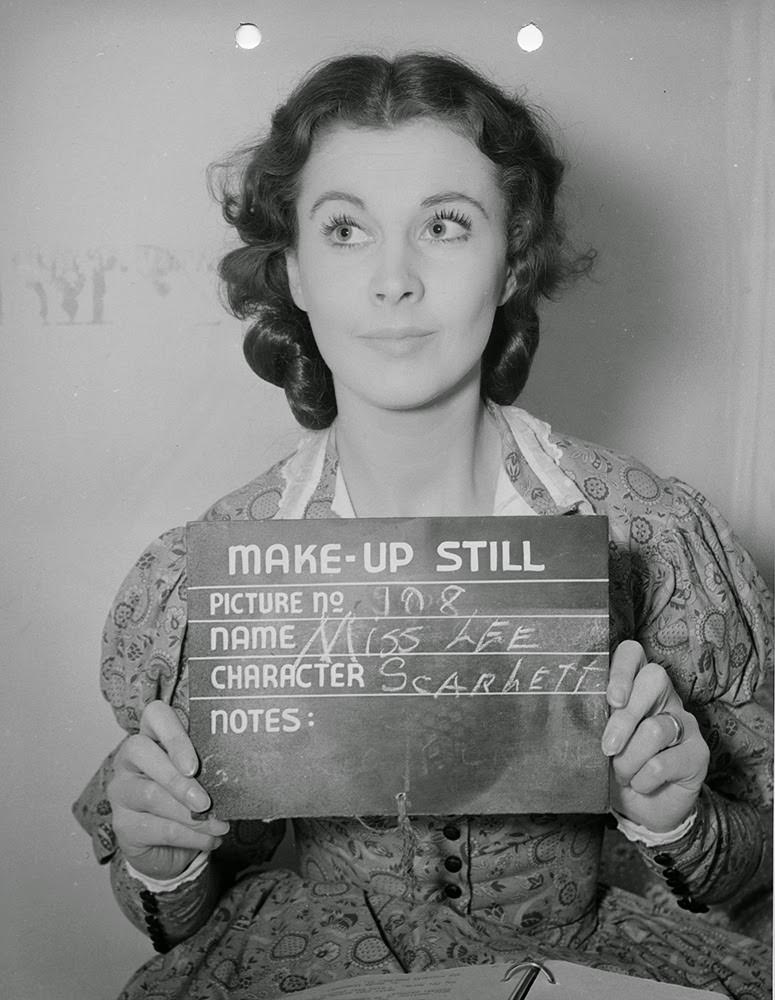

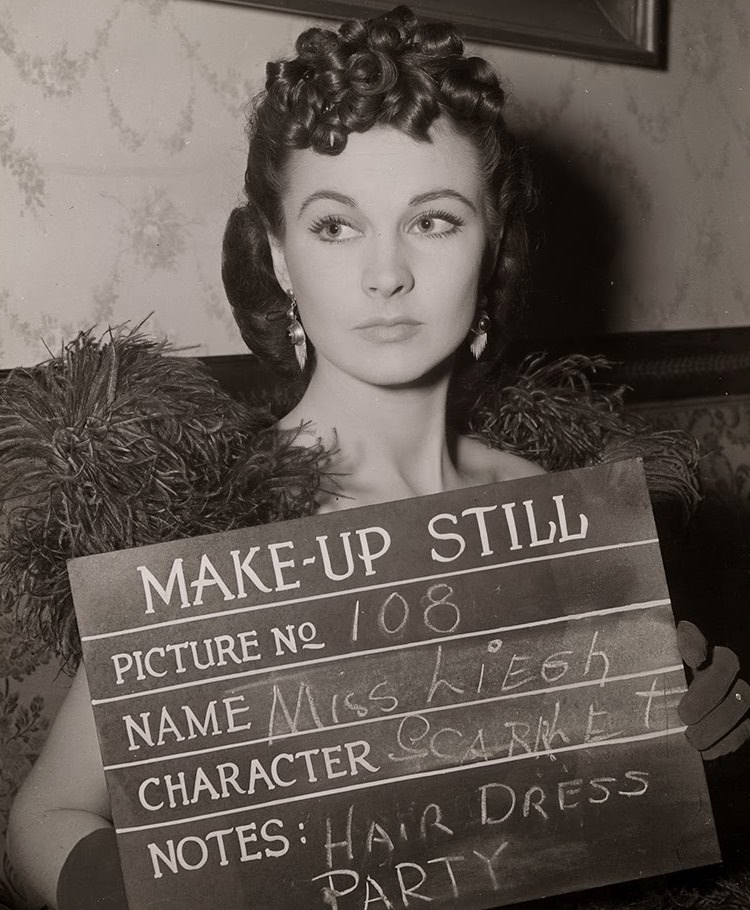

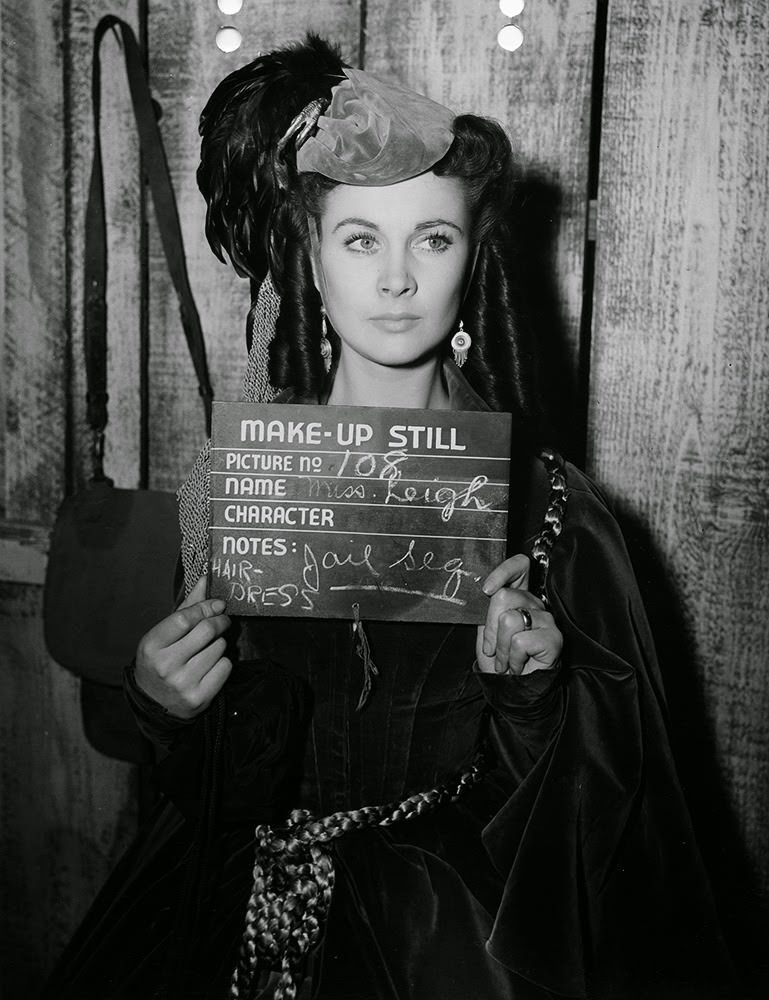

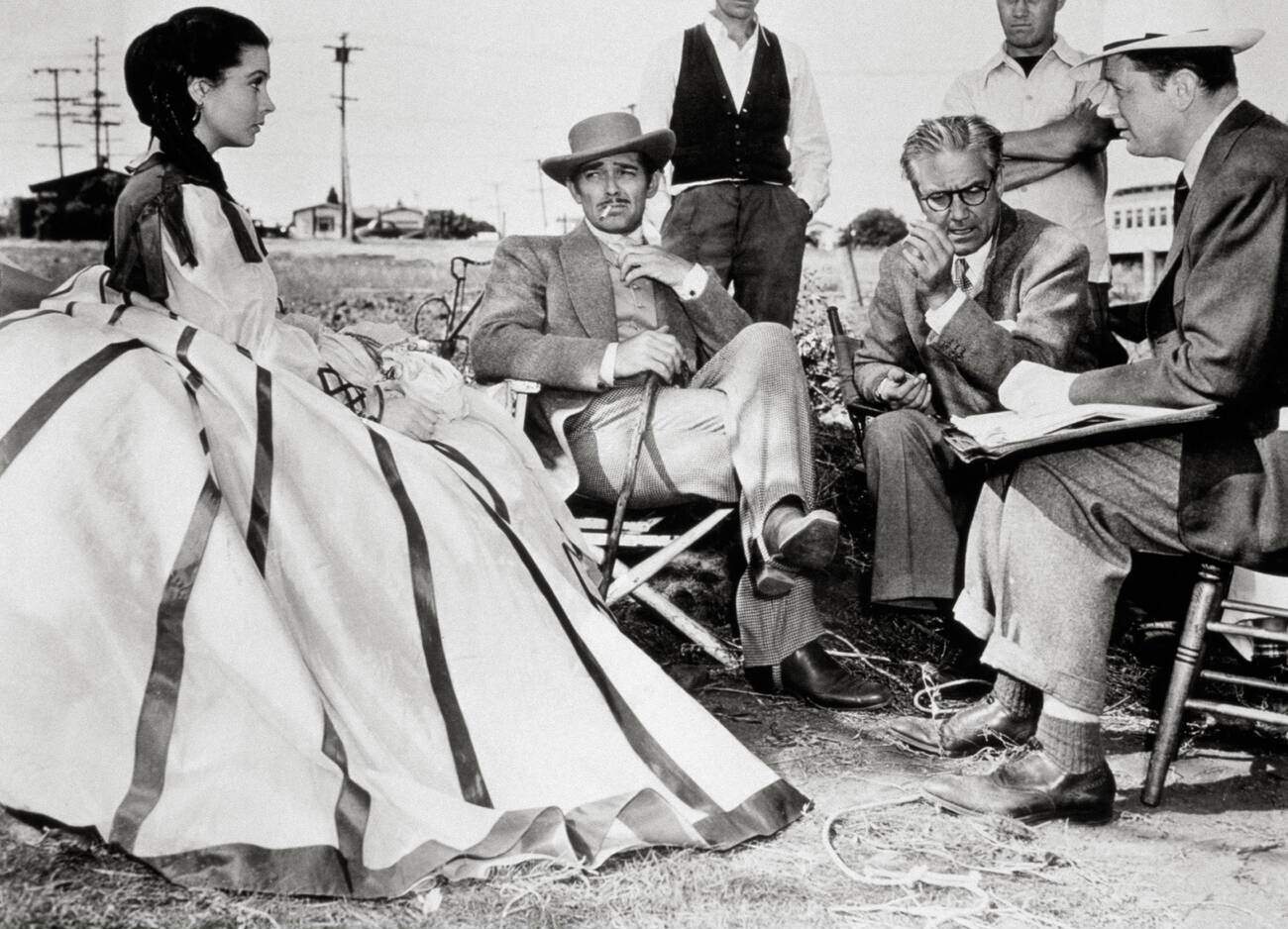

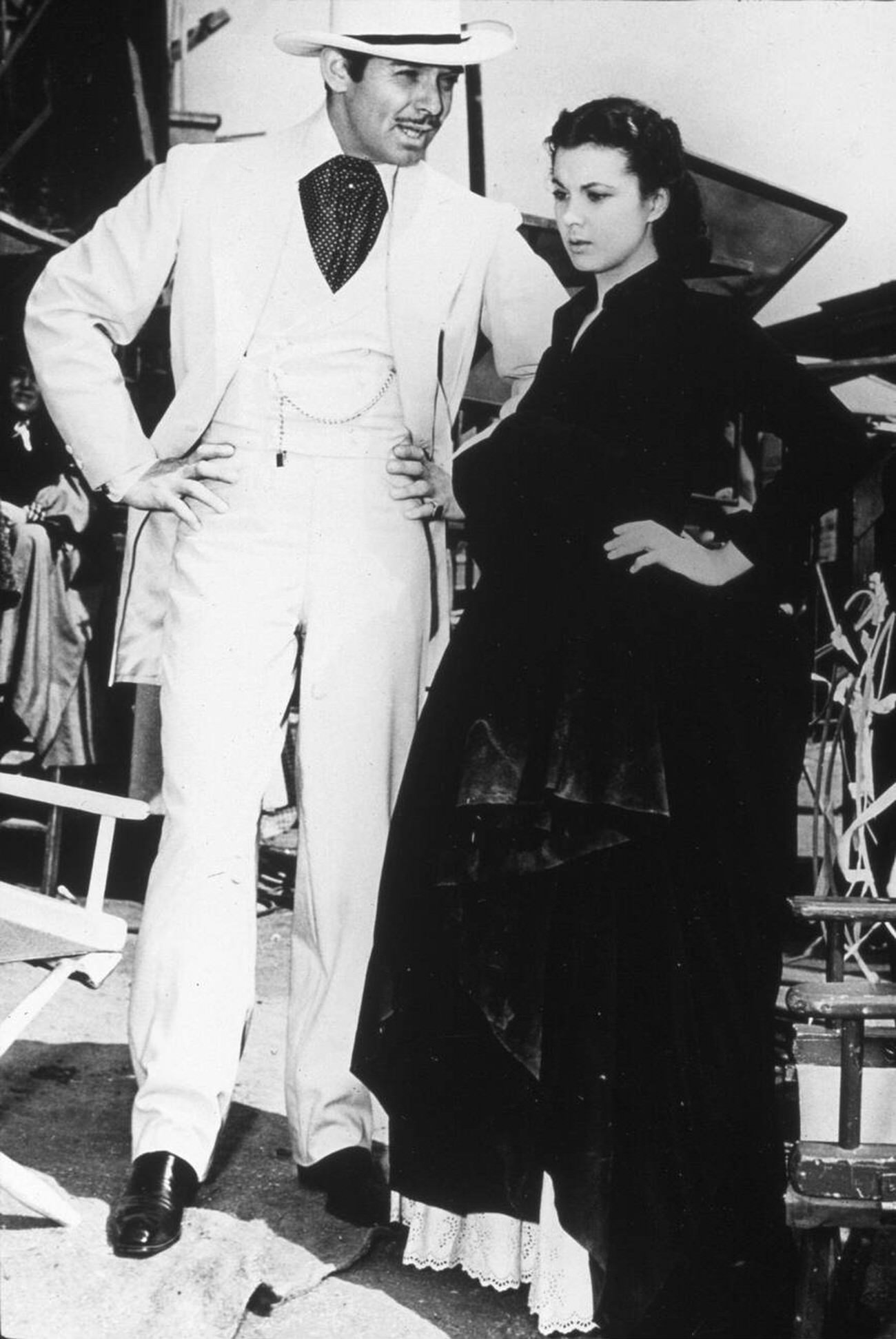

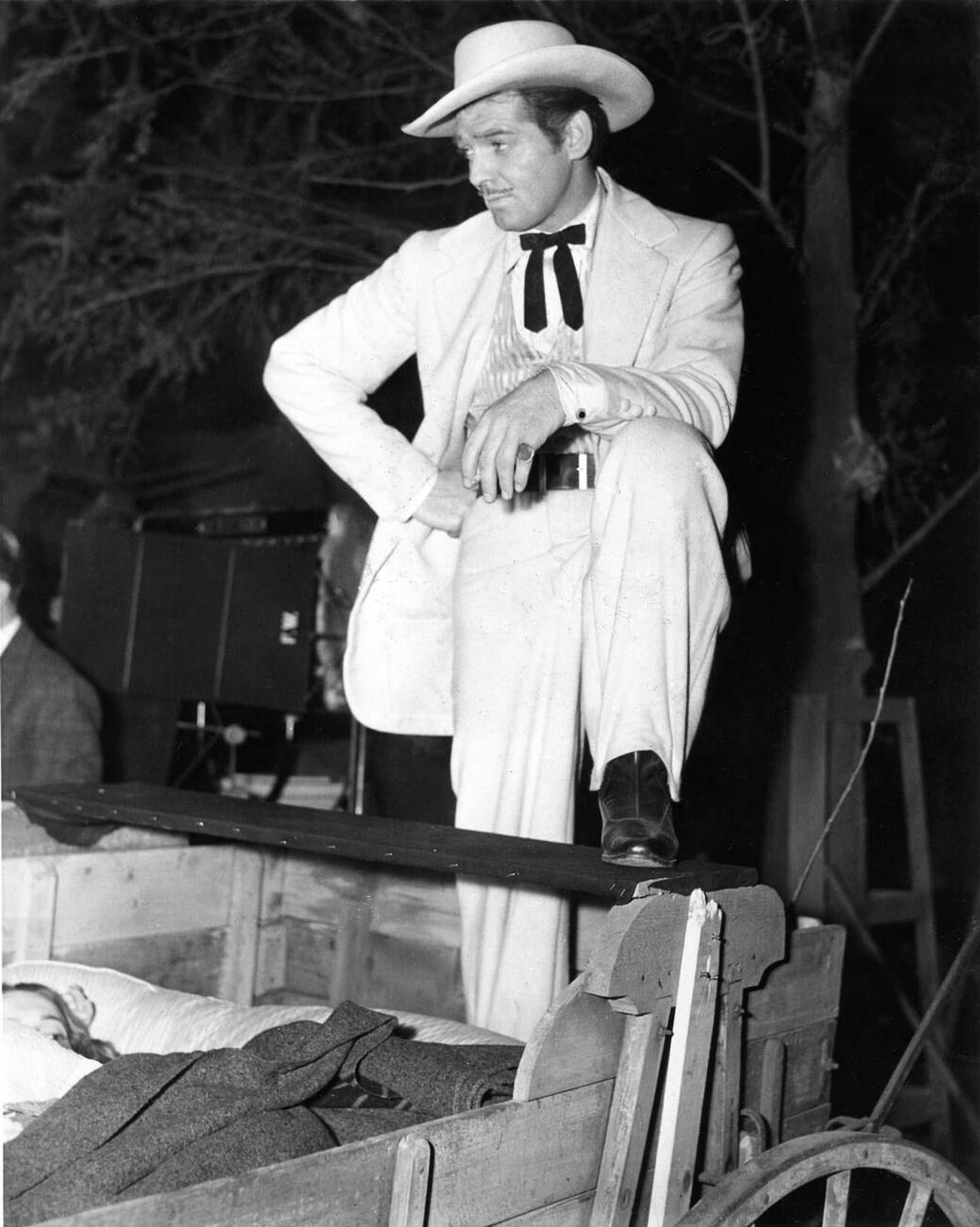

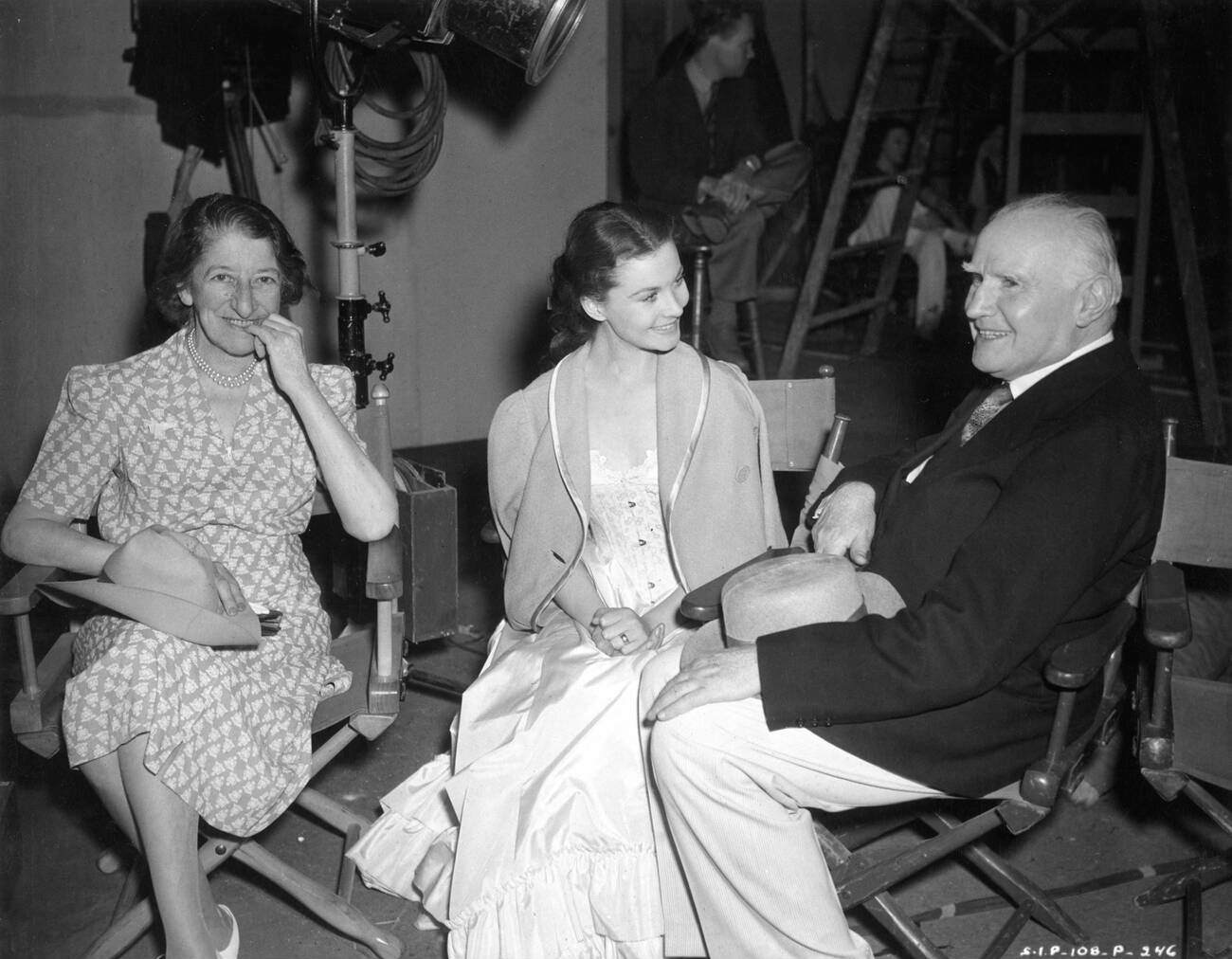

One of the most publicized aspects of the production was the casting of Scarlett O’Hara. Selznick’s search for the perfect actress turned into a nationwide event. Many prominent actresses, including Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn, were considered. Ultimately, Vivien Leigh, a relatively unknown British actress, won the role. Her chemistry with Clark Gable, who was cast as Rhett Butler, was evident from the start and became one of the film’s defining features.

Read more

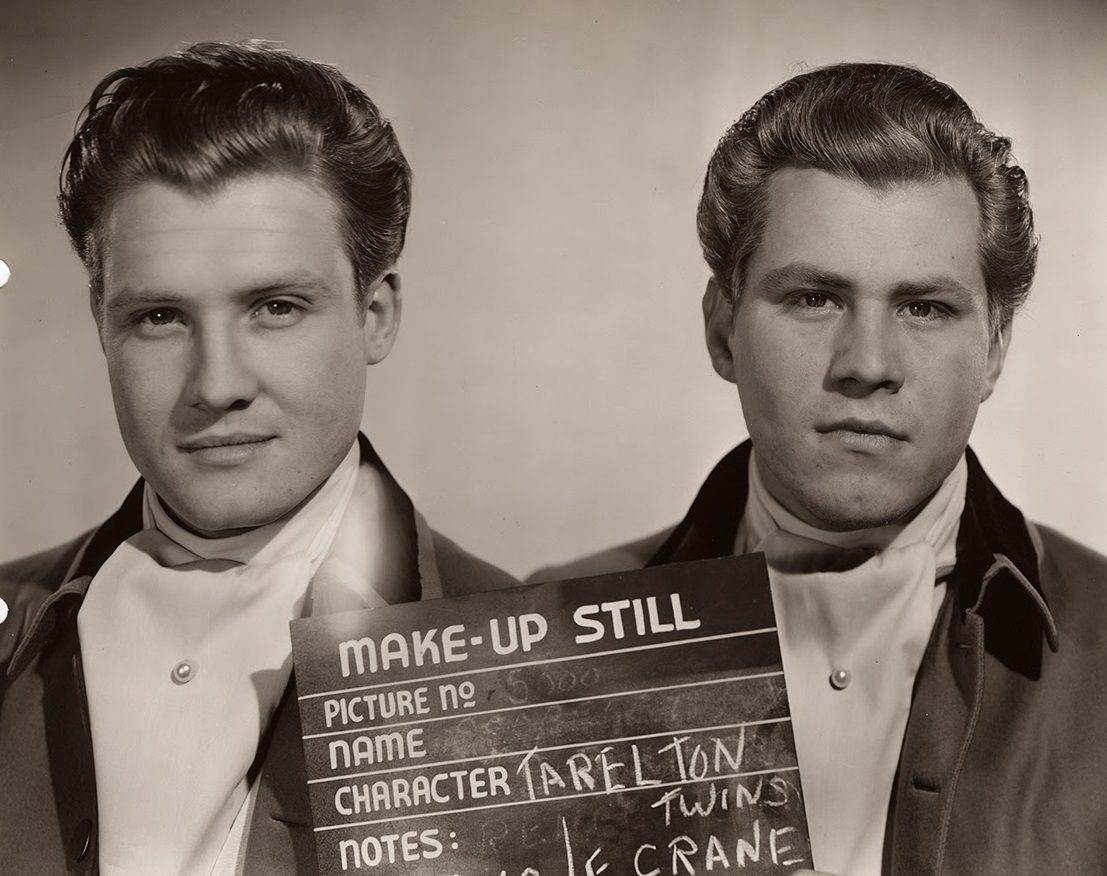

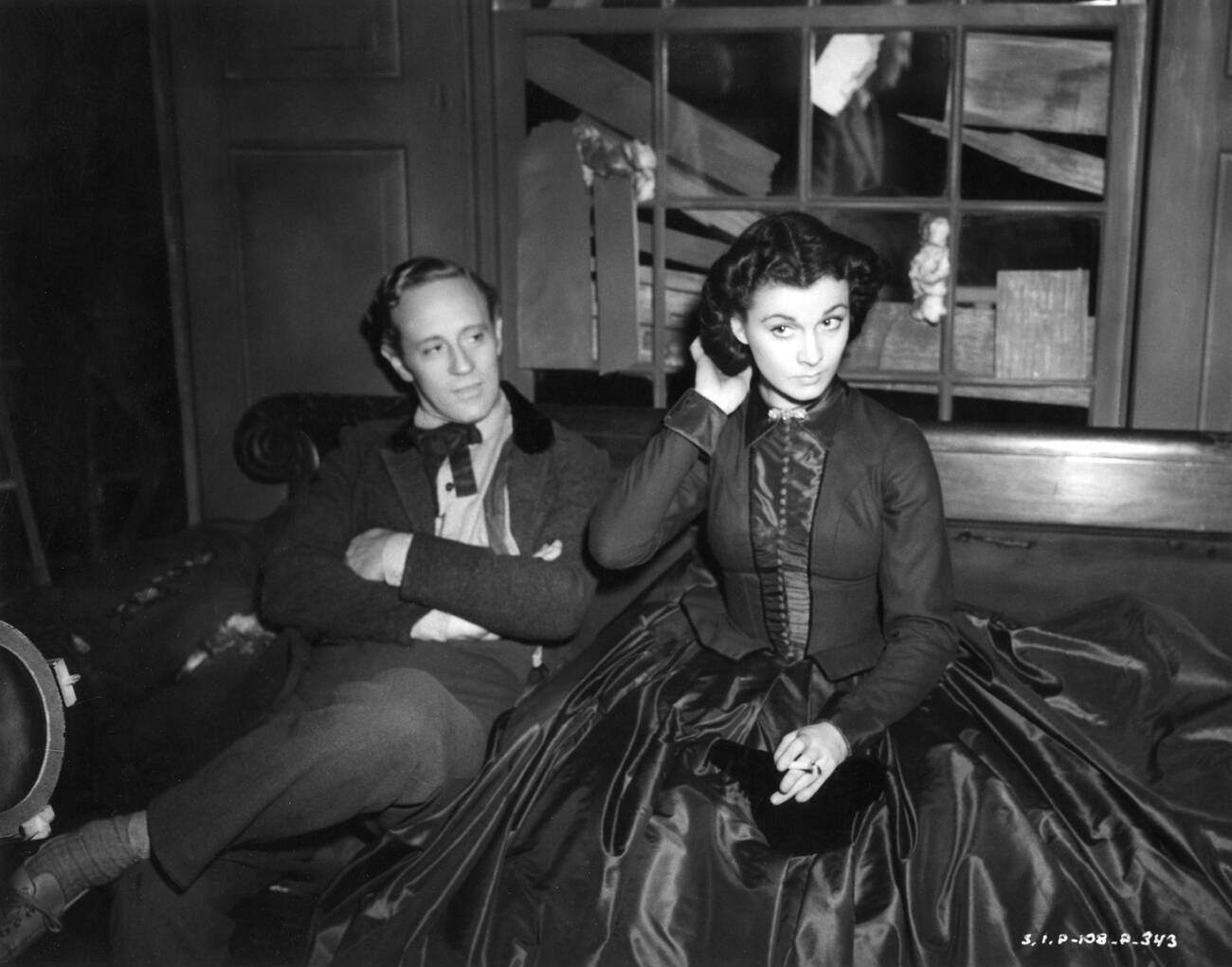

The casting process for other characters was also rigorous. Leslie Howard was selected to play Ashley Wilkes, while Olivia de Havilland took on the role of Melanie Hamilton. Each actor brought their unique interpretation to their roles, adding depth and nuance to the film’s characters. Casting Hattie McDaniel as Mammy was a historic decision, as she became the first African American to win an Academy Award for her performance.

Building the World of the Old South

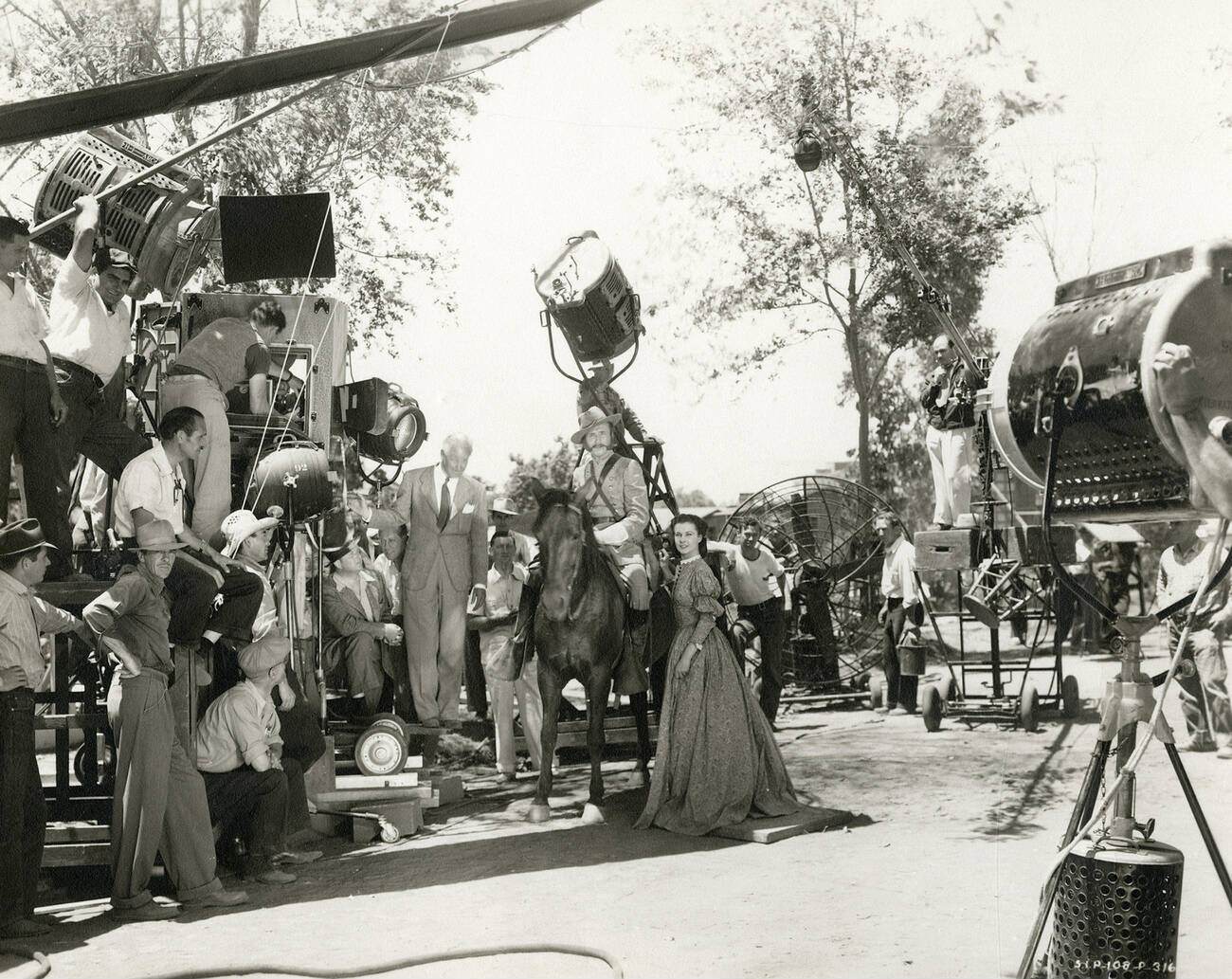

Recreating the world of the Old South was a monumental challenge for the production team. Art director Lyle Wheeler led a team tasked with designing elaborate sets that captured the grandeur and decay of antebellum Georgia. Tara, the O’Hara family plantation, was constructed on a backlot at Selznick International Studios. The mansion’s exteriors were built from wood and plaster, while the interiors were intricately decorated to reflect the period’s elegance.

The famous Twelve Oaks plantation was also an impressive set. Its sweeping staircase and grand rooms showcased the opulence of Southern aristocracy. Many of these sets were reused or repurposed from previous films to save costs, a common practice in Hollywood at the time. For example, the famous burning of Atlanta scene was filmed using old sets from other productions that were set ablaze.

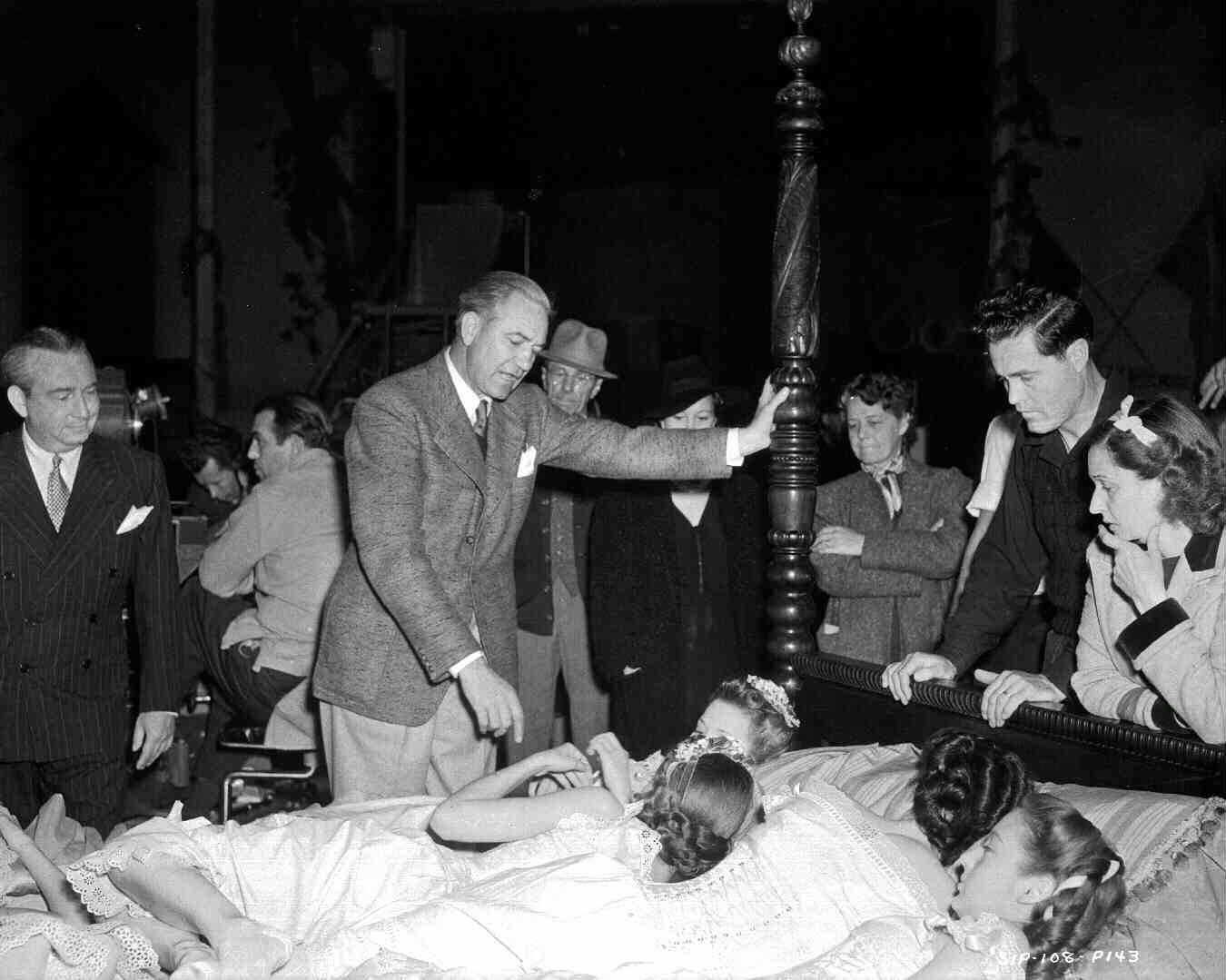

Filming the Iconic Scenes

The production officially began on January 26, 1939. One of the first sequences filmed was the burning of Atlanta, which required immense coordination and technical expertise. Over 10 acres of the studio backlot were used for the scene, with controlled fires consuming sets while actors performed their roles amidst the chaos. The use of real flames and large-scale destruction added an unparalleled sense of realism.

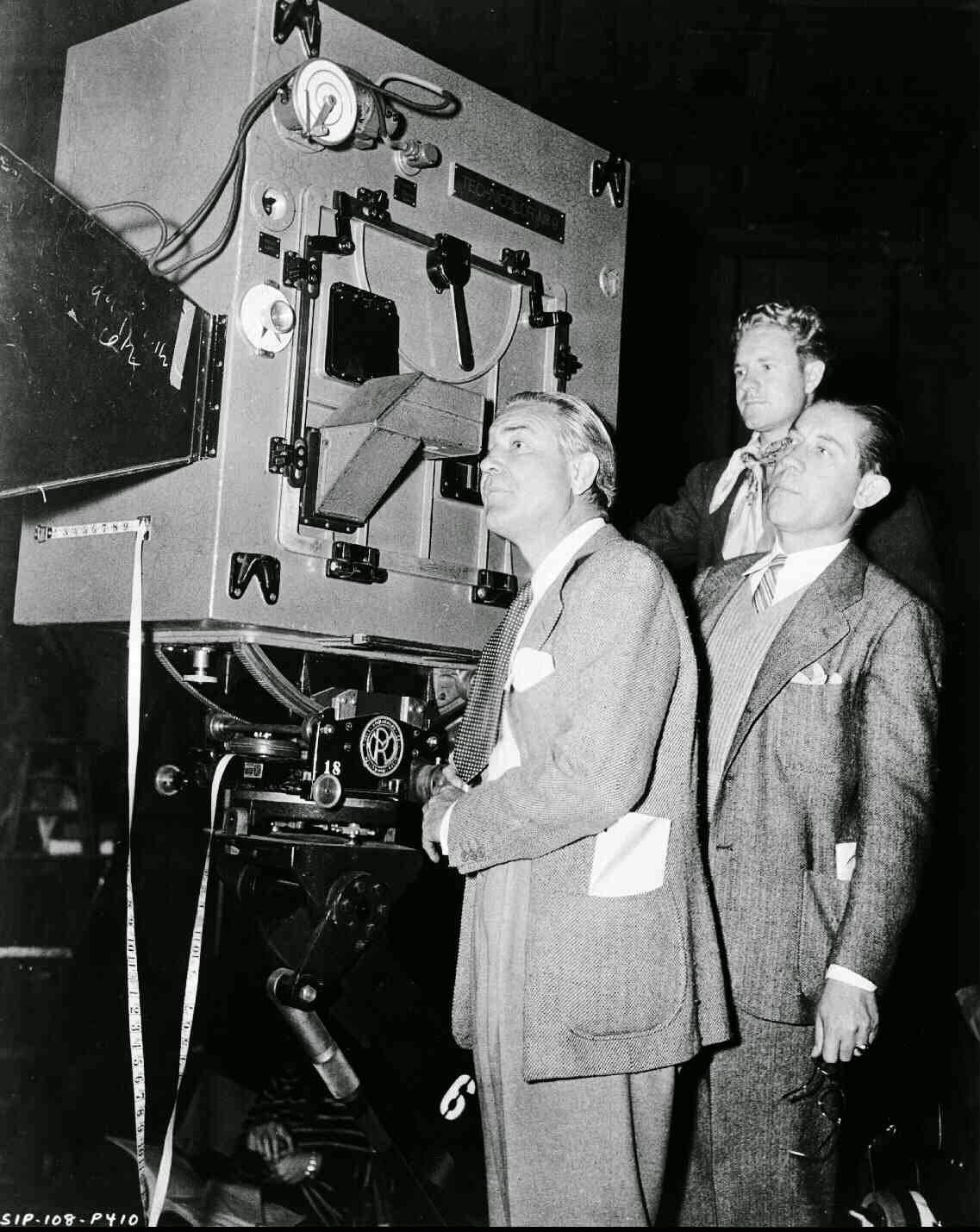

Technicolor was another groundbreaking element of the film. Cinematographer Ernest Haller and color consultant Natalie Kalmus worked together to create vibrant, emotionally resonant visuals. The decision to shoot in Technicolor added complexity to the production, as lighting and costume colors had to be meticulously planned to ensure they appeared correctly on screen. Scarlett’s green dress, for example, was dyed multiple times to achieve the perfect shade under the studio lights.

Many scenes required large numbers of extras, especially during the war sequences. For the scene depicting wounded Confederate soldiers sprawled across a railway station, the production used over 1,500 extras. The image of Scarlett walking among the injured and dead became one of the film’s most iconic moments.

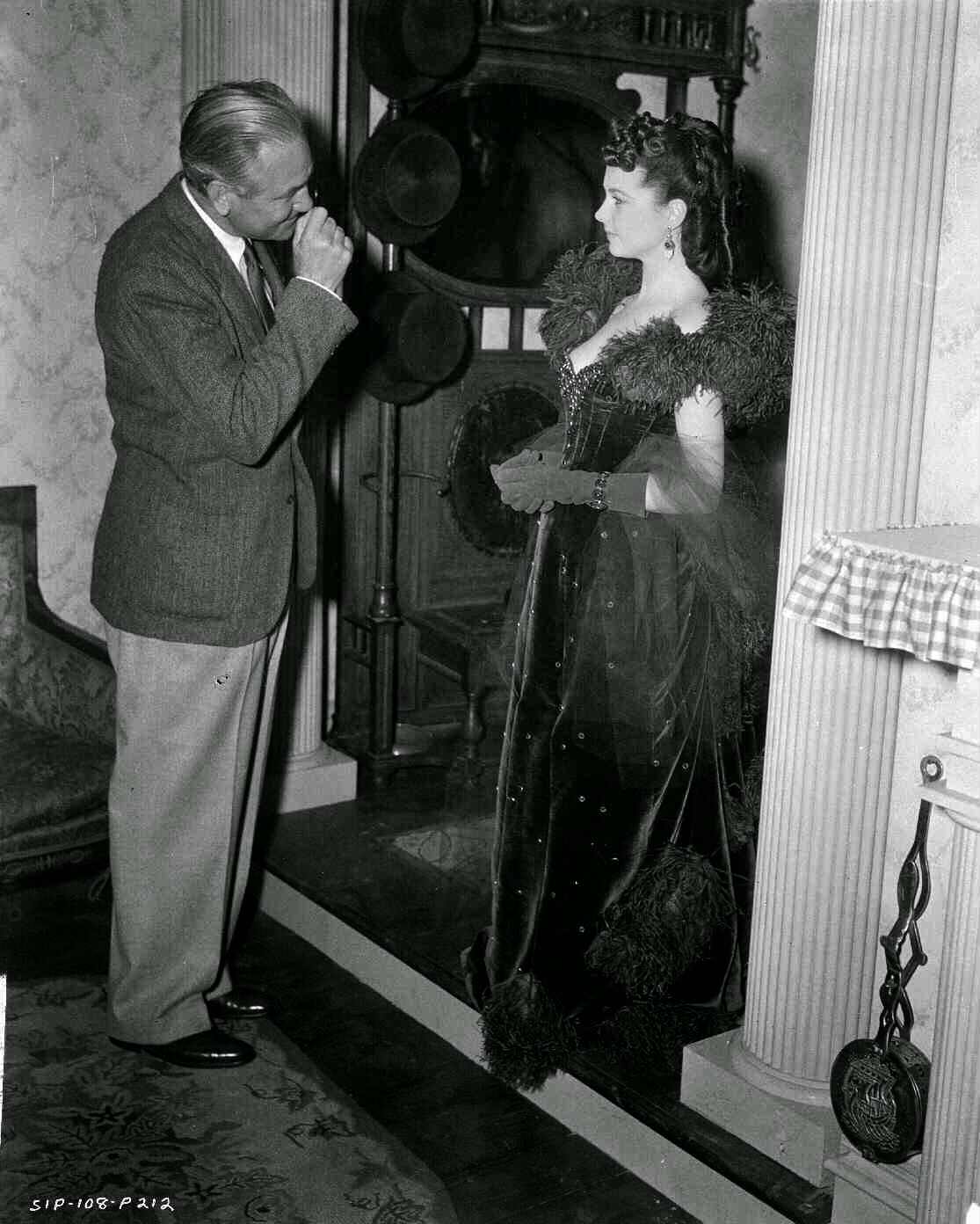

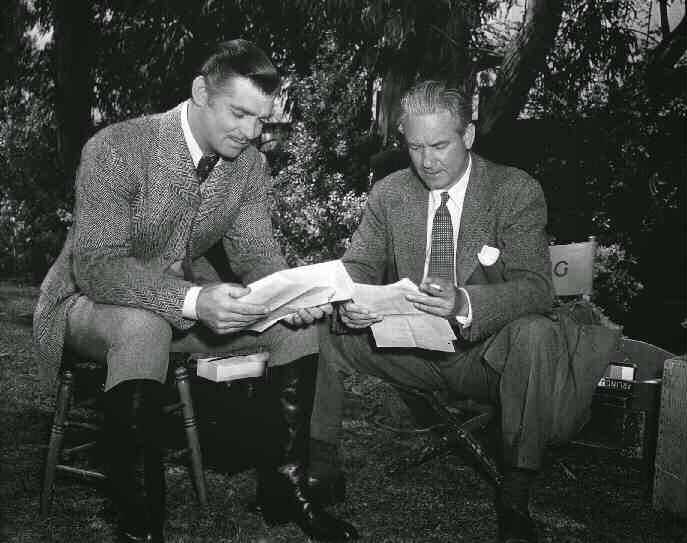

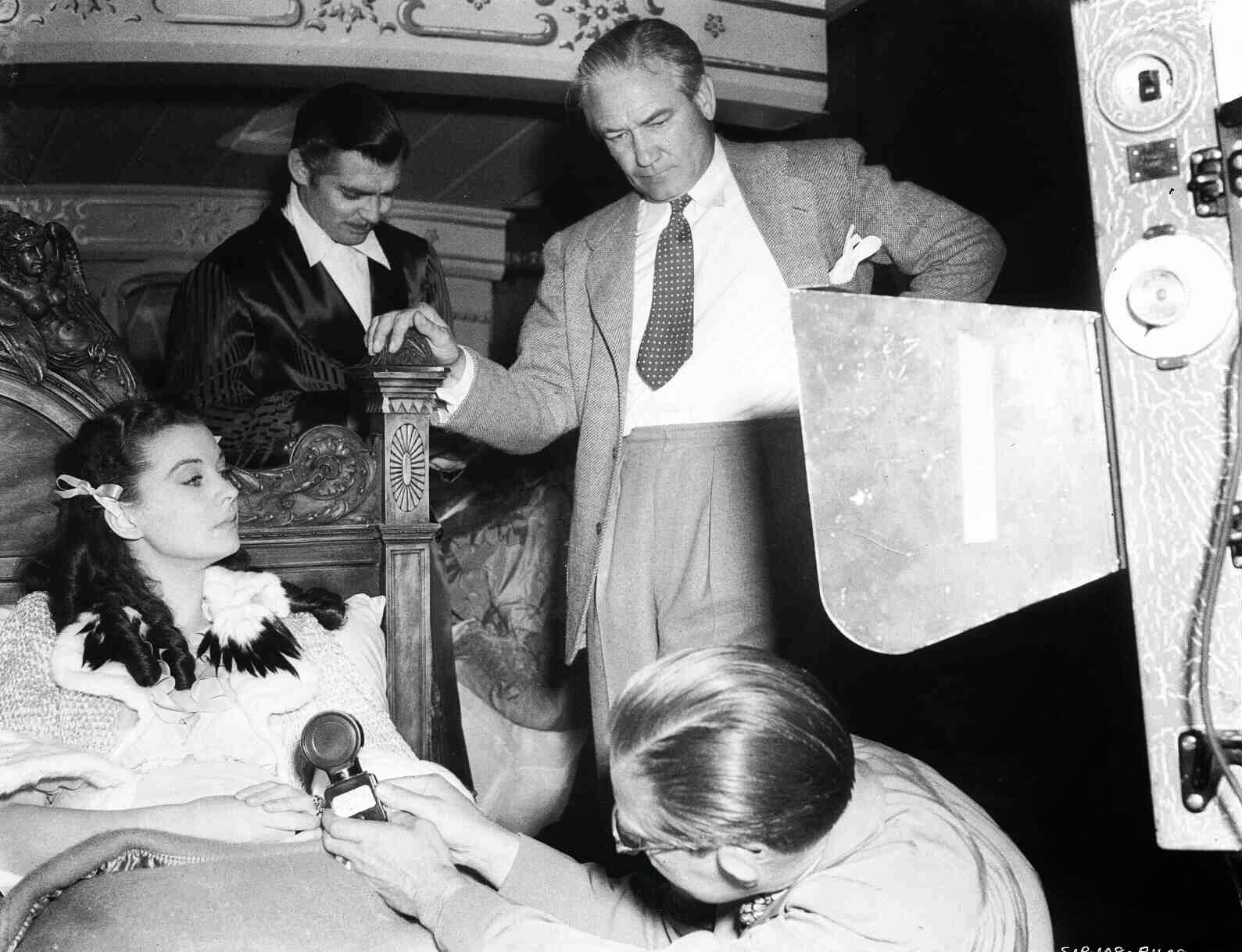

Victor Fleming is credited as the director, but the production involved several other filmmakers. George Cukor was originally hired but was replaced early in the production due to creative differences with Selznick. Fleming, known for his work on The Wizard of Oz, was brought in to take over. His assertive and decisive style helped steer the film through its challenging shoot.

However, the strain of the production took its toll on Fleming. At one point, he temporarily left the project due to exhaustion, and Sam Wood stepped in to direct a few scenes. Despite these difficulties, the finished product remained cohesive, a testament to the professionalism of the cast and crew.

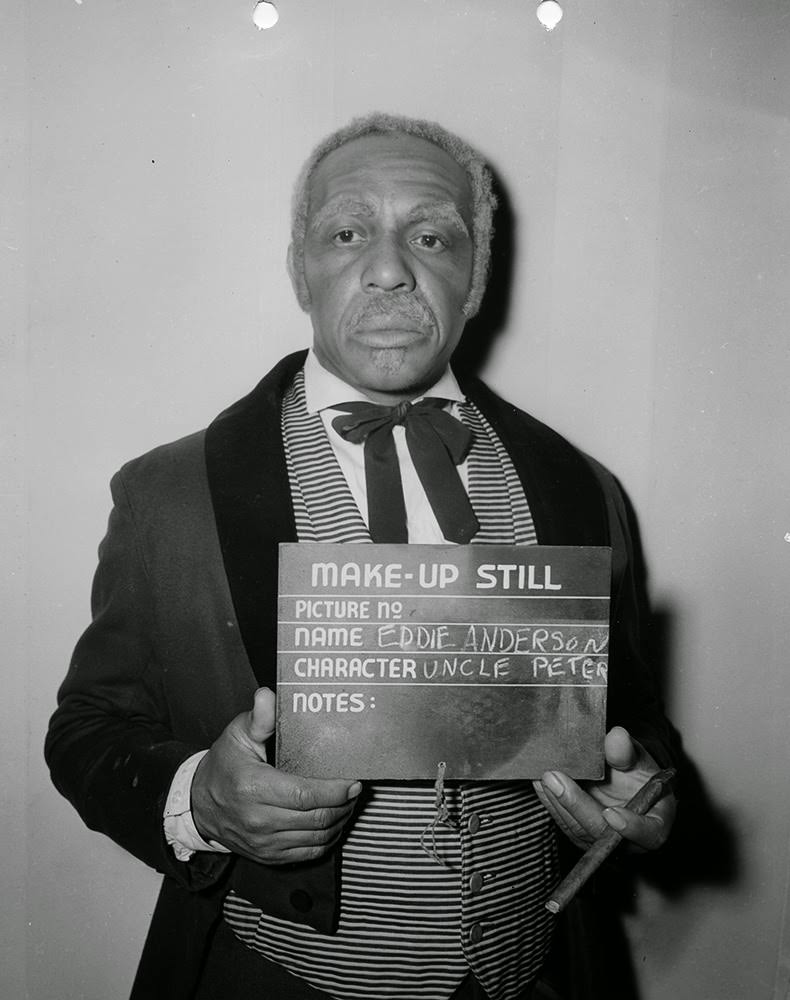

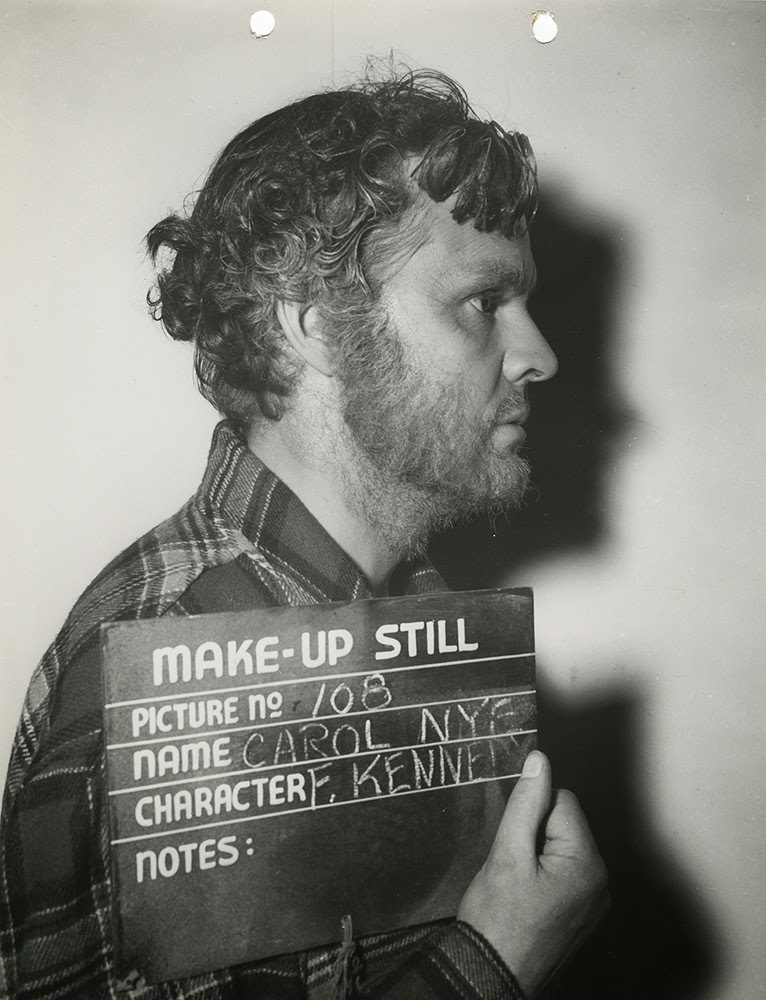

Costumes and Makeup

Costume designer Walter Plunkett played a crucial role in bringing the period to life. He created over 5,000 costumes for the film, including Scarlett’s iconic wardrobe. The green curtain dress and the red gown worn at Ashley’s birthday party became cultural touchstones. Plunkett’s designs balanced historical accuracy with dramatic flair, ensuring the costumes enhanced the storytelling.

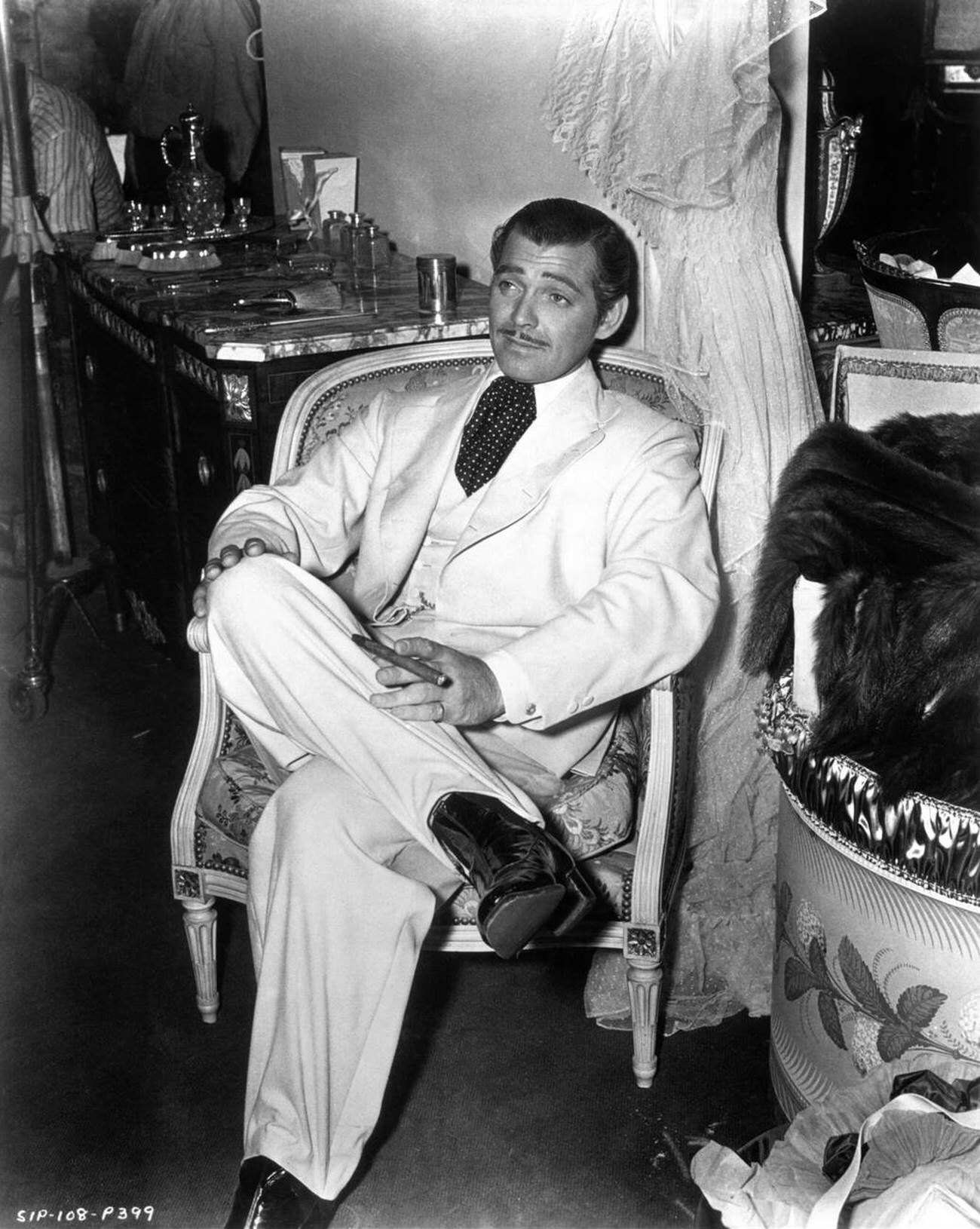

Makeup artists also worked meticulously to transform the actors into their characters. Leigh’s appearance was adjusted throughout the film to reflect Scarlett’s journey from a pampered Southern belle to a resilient survivor. Gable’s trademark mustache and polished look added to Rhett Butler’s charm and charisma.

Challenges on Set

The production faced numerous challenges, from weather delays to on-set tensions. Vivien Leigh’s determination and perfectionism occasionally clashed with her co-stars. Gable’s initial reluctance to take on the part of Rhett was overcome by his professionalism and natural charisma, which brought the character to life.

Selznick’s insistence on perfection added to the pressures of the shoot. He was known for micromanaging and frequently rewriting scenes. While this caused delays, it also ensured that the film met his high standards. The actors often worked long hours, with some scenes requiring dozens of takes to achieve the desired effect.

Post-Production and Premiere

Editing Gone with the Wind was a complex process. The film’s final runtime was over four hours, making it one of the longest Hollywood productions of its time. Editor Hal C. Kern and assistant editor James E. Newcom had to carefully balance pacing while preserving the story’s epic scope. The musical score, composed by Max Steiner, added emotional depth to the film, with themes that have since become iconic.

The film’s premiere on December 15, 1939, in Atlanta, Georgia, was a grand event. Thousands of fans gathered to catch a glimpse of the stars, and the city embraced the occasion with parades and celebrations. The event underscored the film’s significance as a cultural milestone, even before it reached general audiences.