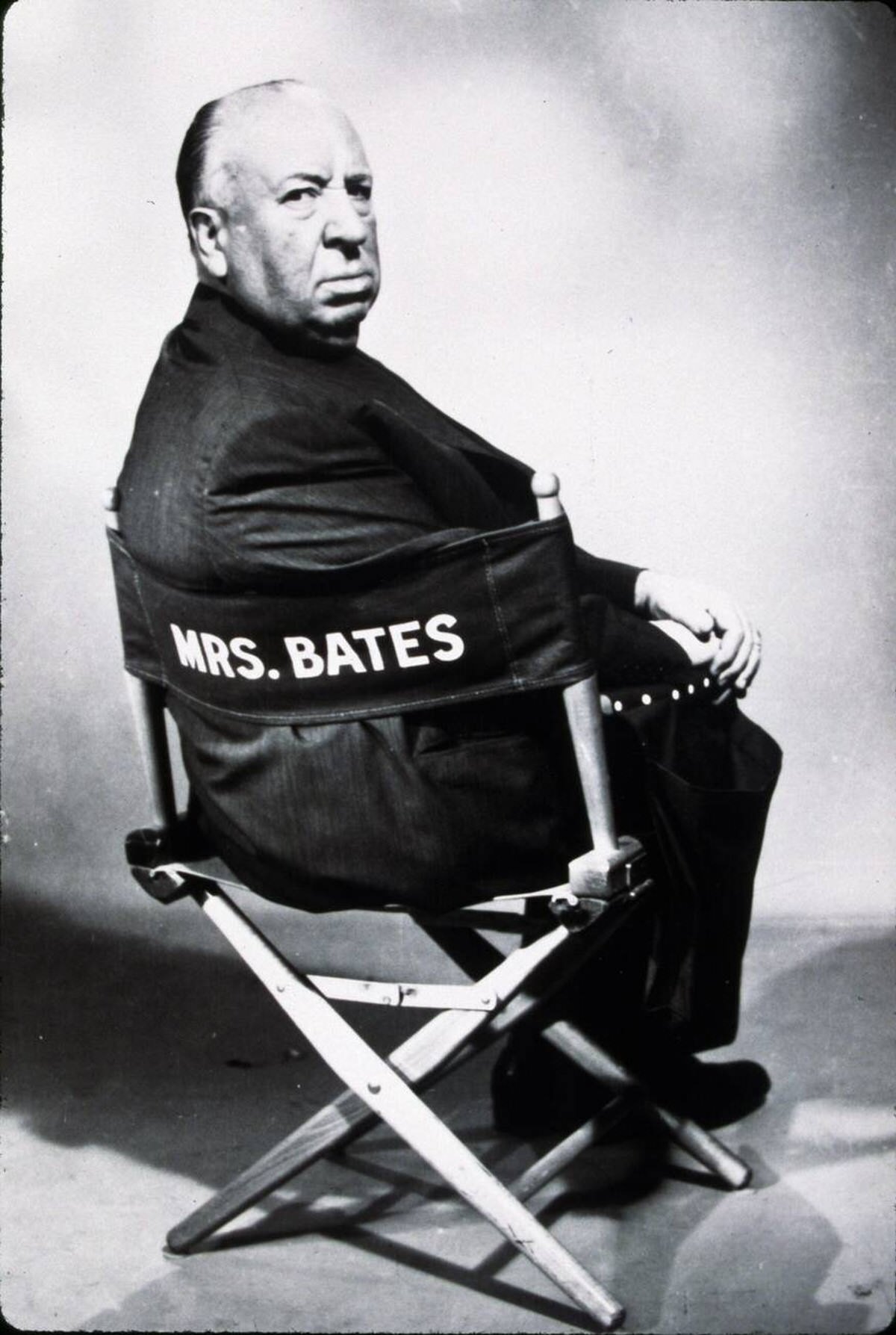

In 1960, Alfred Hitchcock released Psycho, a film that broke many rules of mainstream cinema. At the time, Hitchcock was already famous for polished thrillers like Rear Window and North by Northwest. With Psycho, he chose a darker story and a harsher tone. The project began as a risky move that challenged studio expectations and audience comfort.

Choosing the Story

Hitchcock discovered Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel Psycho soon after its release. The book was loosely based on the crimes of Ed Gein, a murderer from rural Wisconsin. The story focused on Norman Bates, a lonely man living beside an isolated motel with his dead, controlling mother dominating his life. Hitchcock saw strong suspense in the simple setting and the damaged psychology of its characters.

To avoid attention from rival studios, Hitchcock quietly bought the film rights. He ordered most copies of the novel removed from stores. This step helped protect the plot twists from public knowledge before the film’s release.

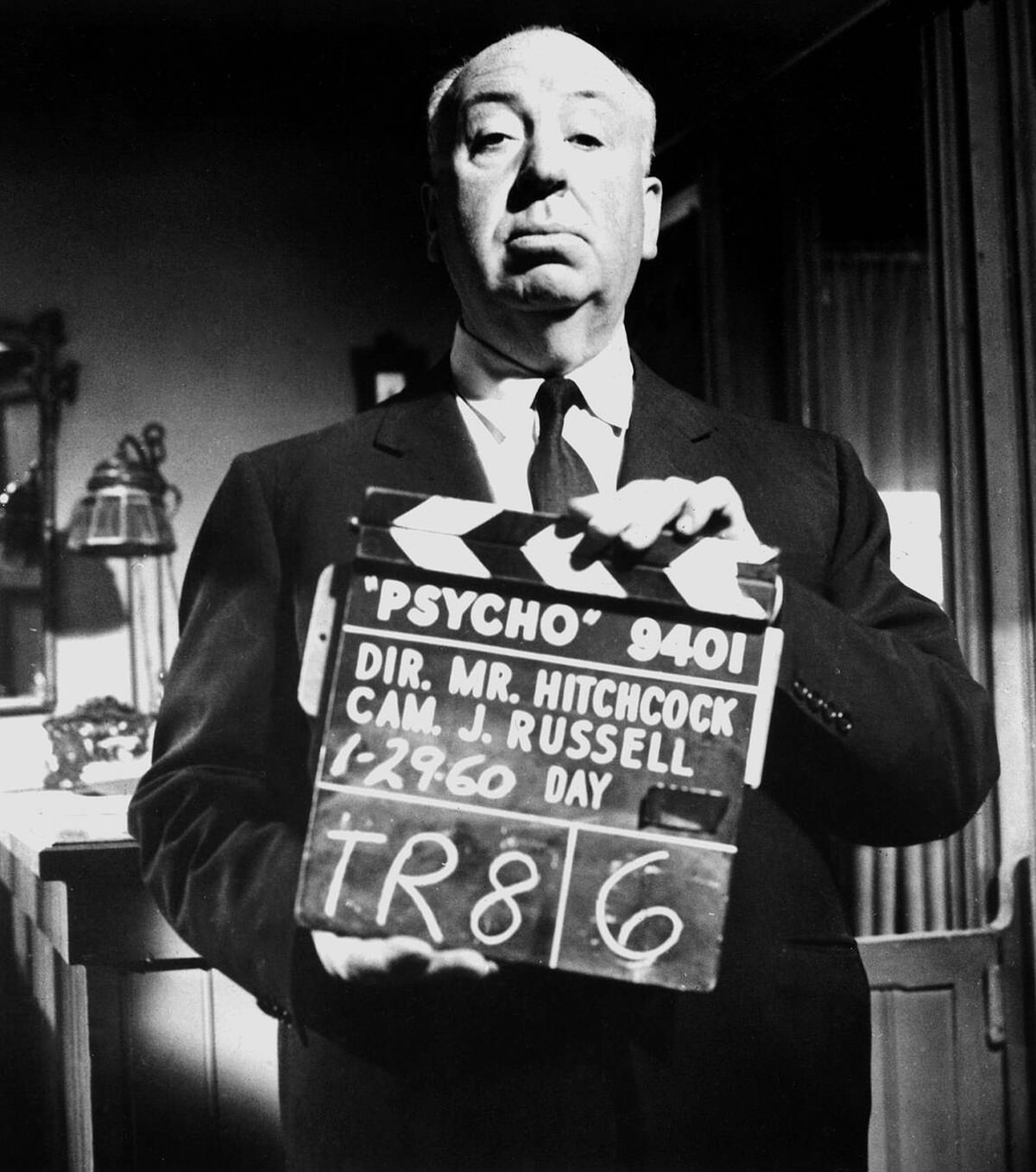

Financing and Production Control

Major studios viewed the story as disturbing and unsuitable for a prestige film. They objected to the violence, sexual themes, and lack of a traditional hero. When Paramount refused to fully fund the project, Hitchcock paid for the film himself. In return, he gained full creative control.

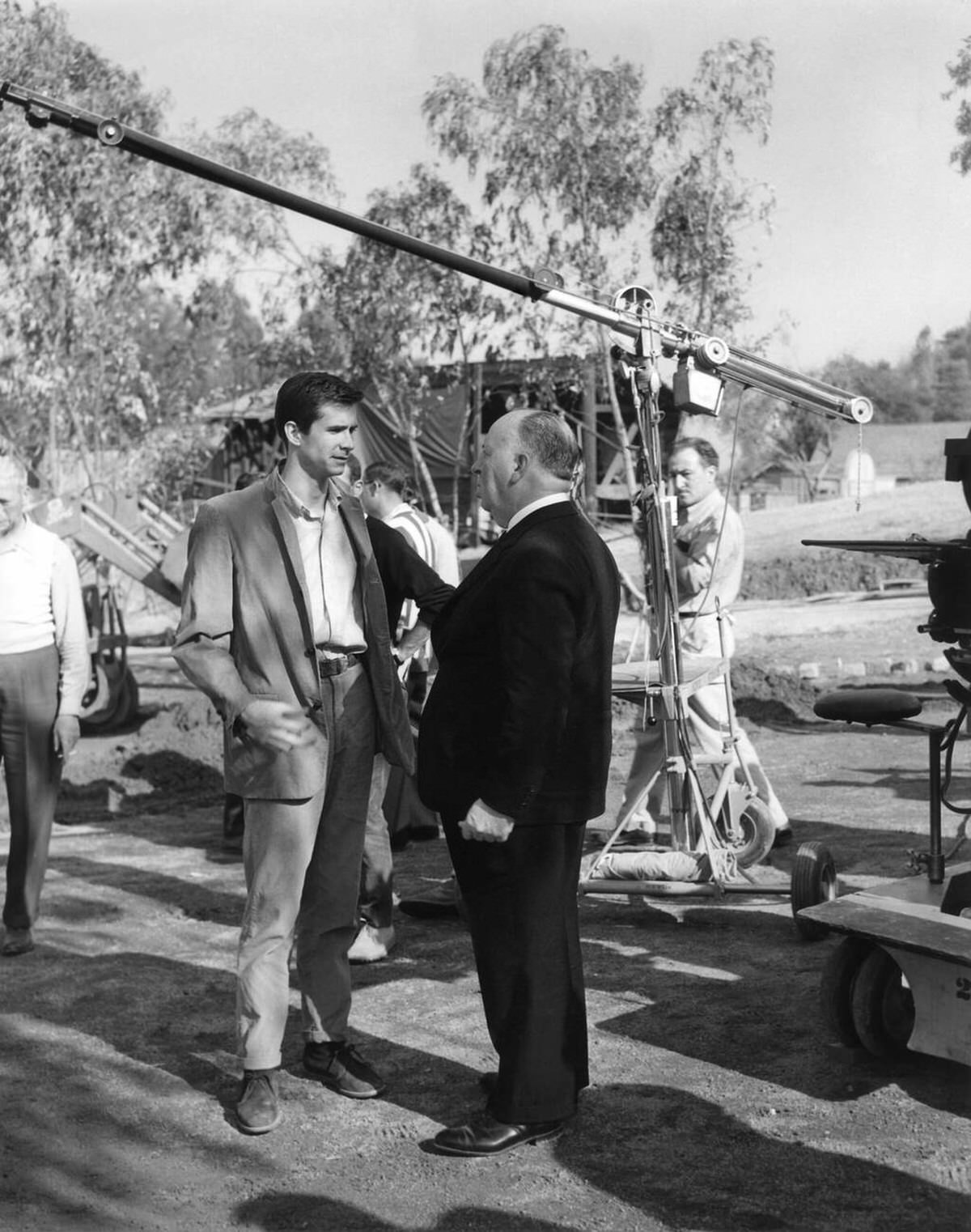

To keep costs low, Hitchcock used the television crew from his show Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The crew was skilled, fast, and used to tight schedules. The film was shot in black and white, which reduced costs and softened the impact of blood on screen.

Read more

Casting Against Expectations

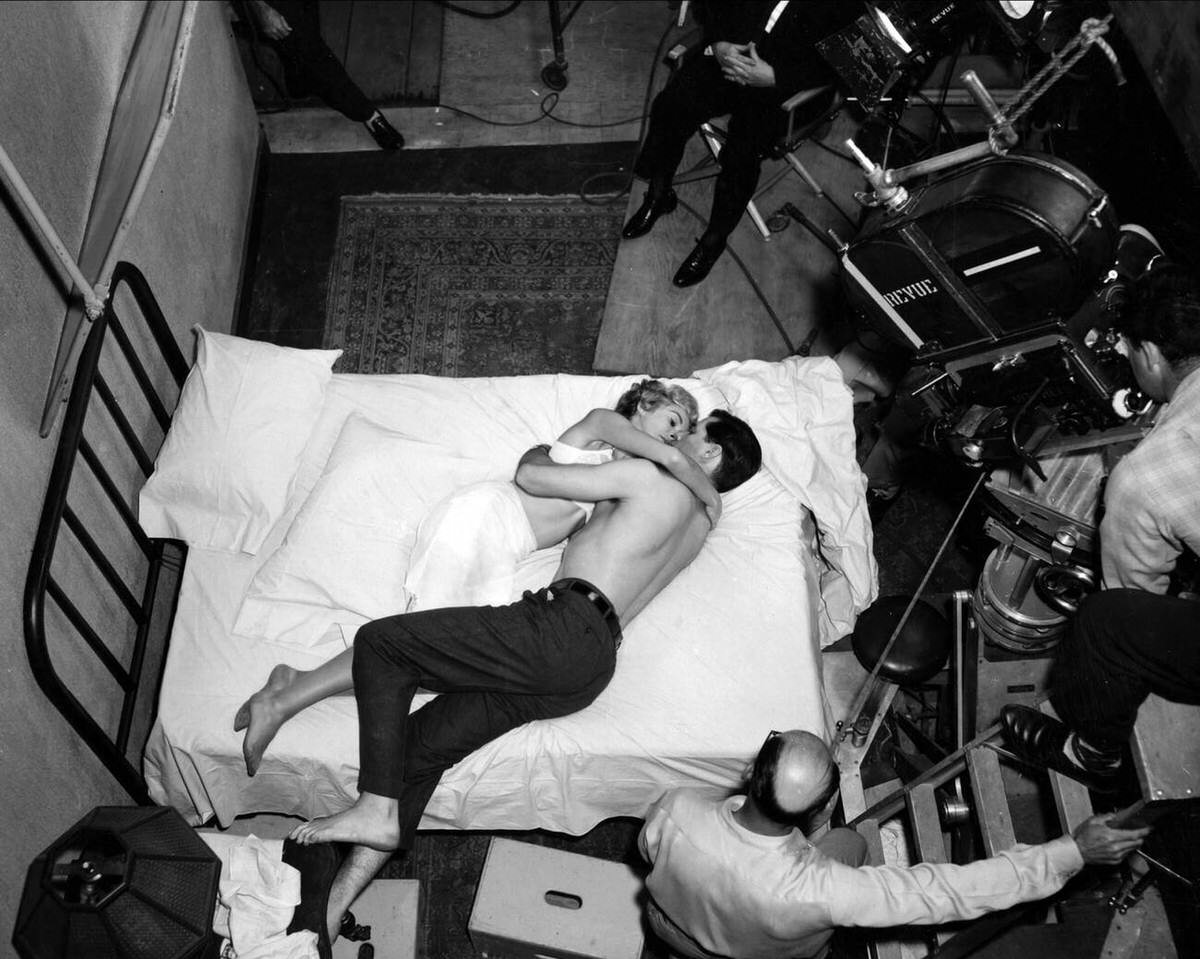

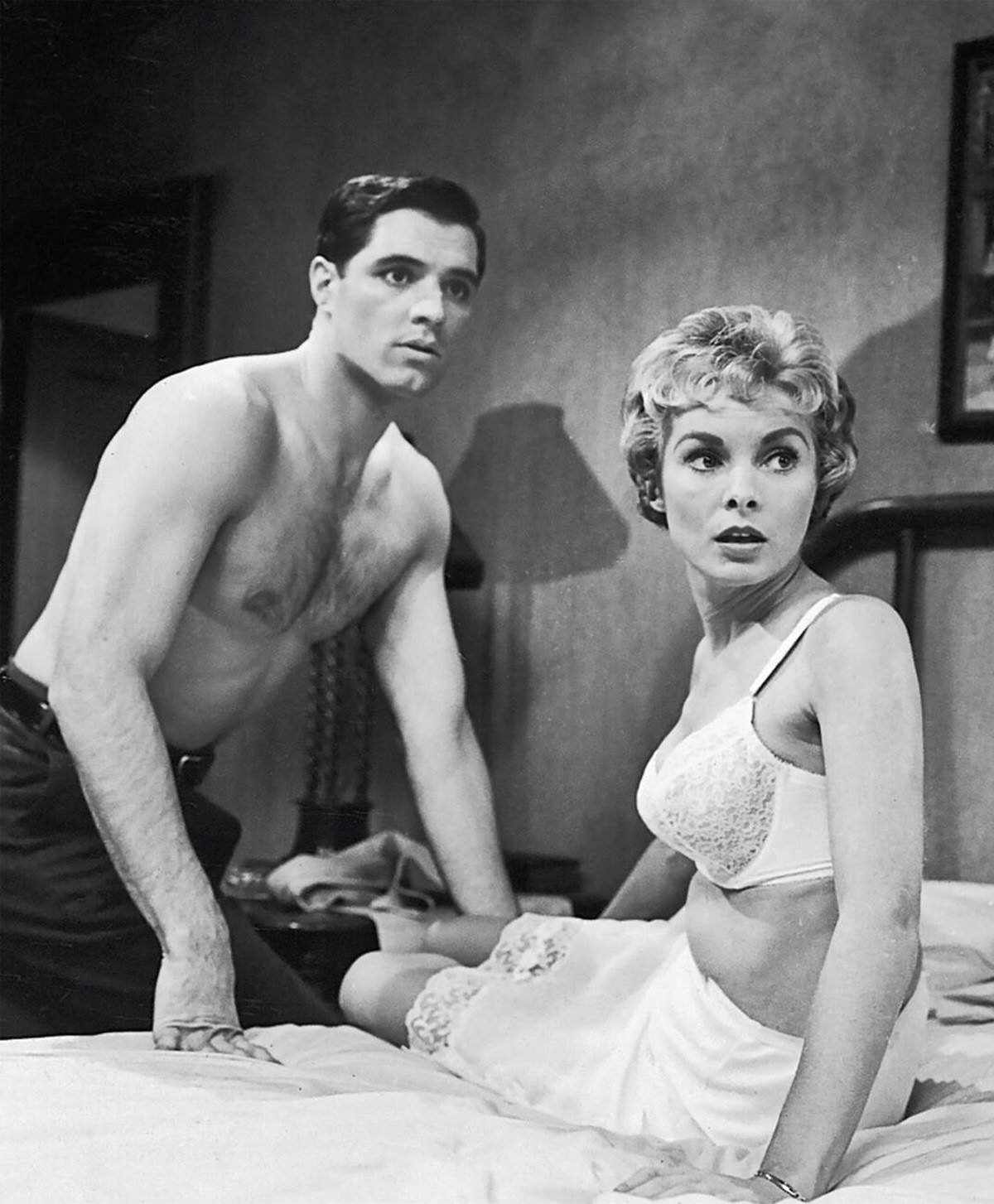

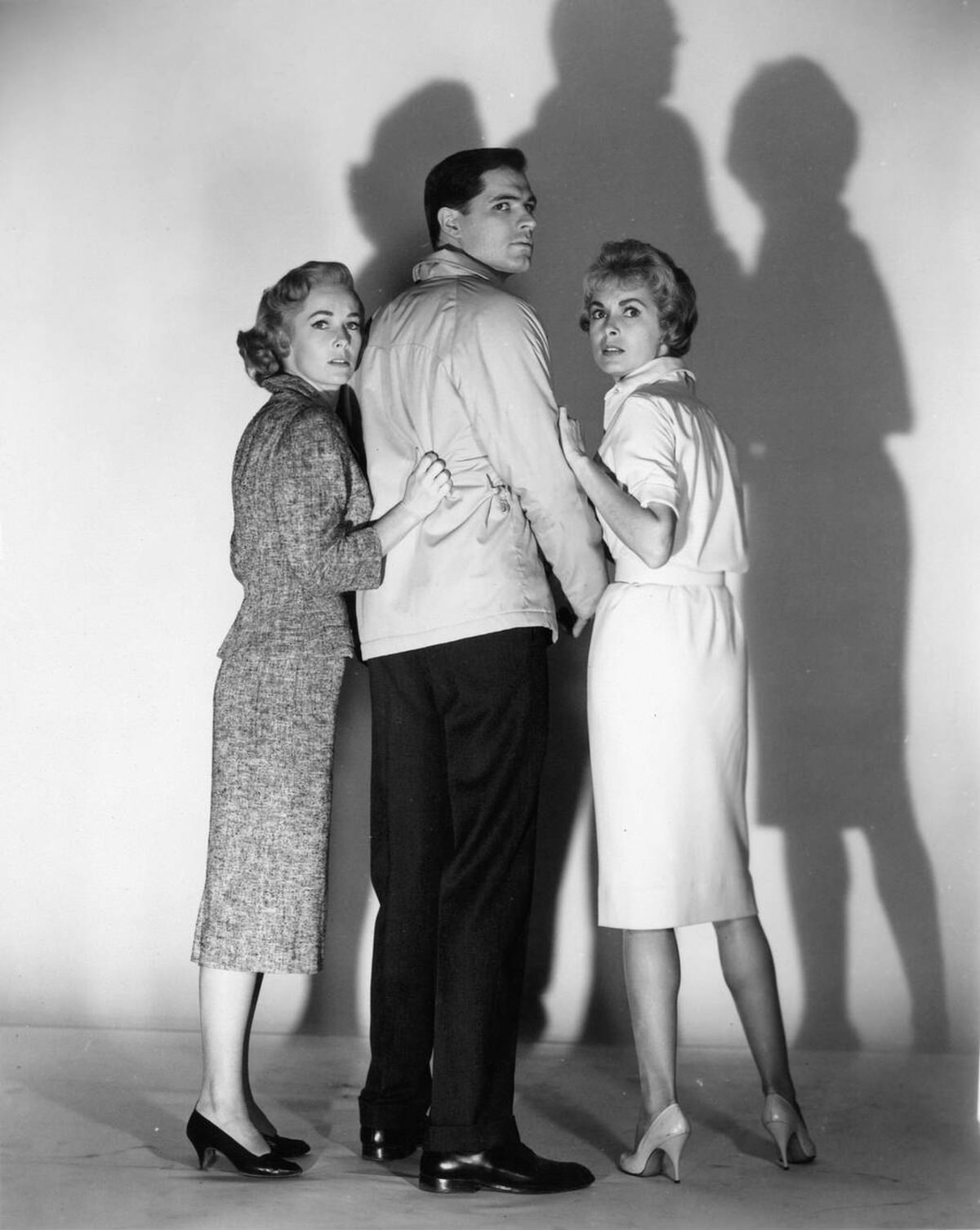

Hitchcock made a bold casting choice by selecting Janet Leigh as Marion Crane. Leigh was a well-known star, and audiences expected her to lead the film. Her character’s early death shocked viewers and removed any sense of safety.

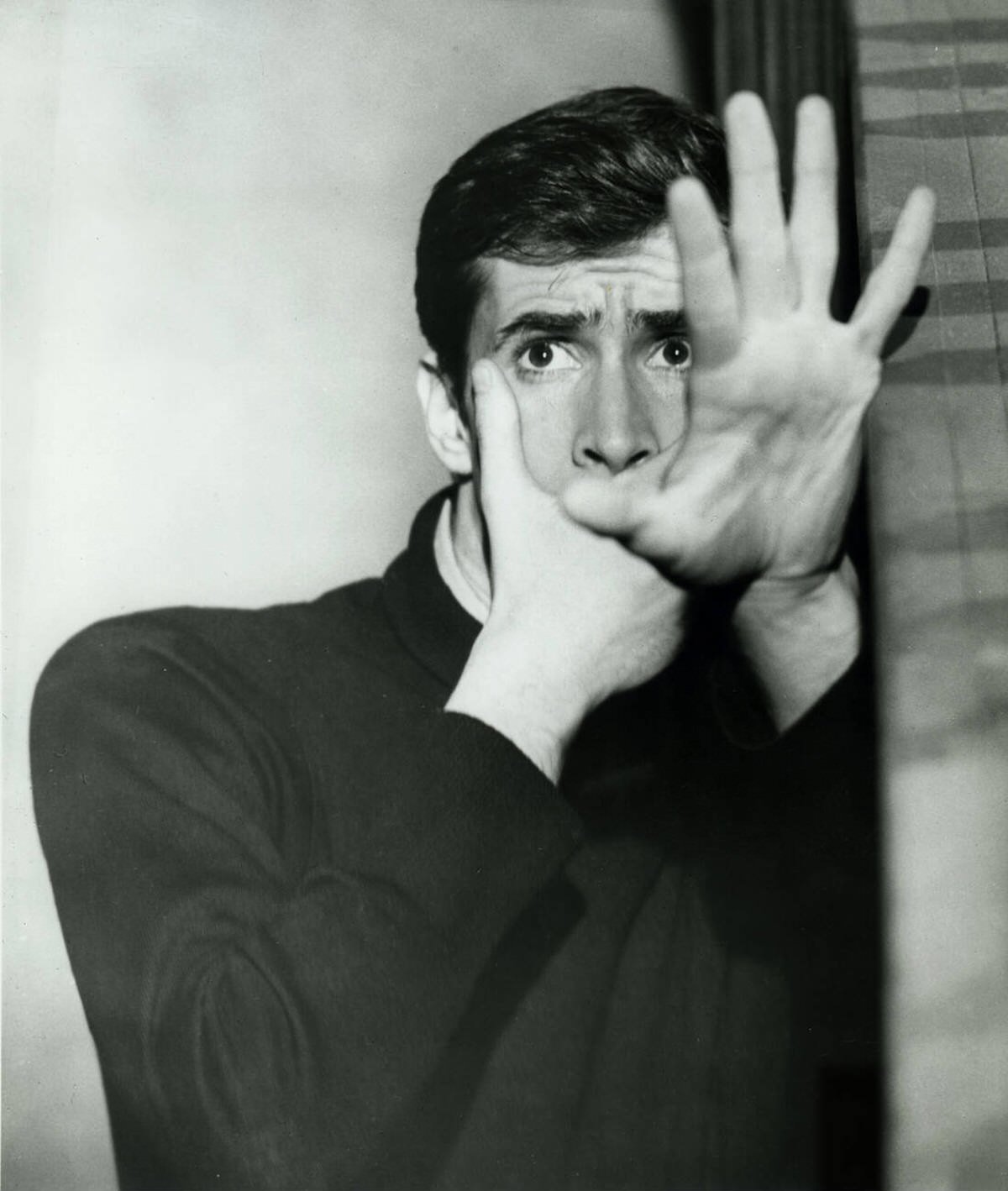

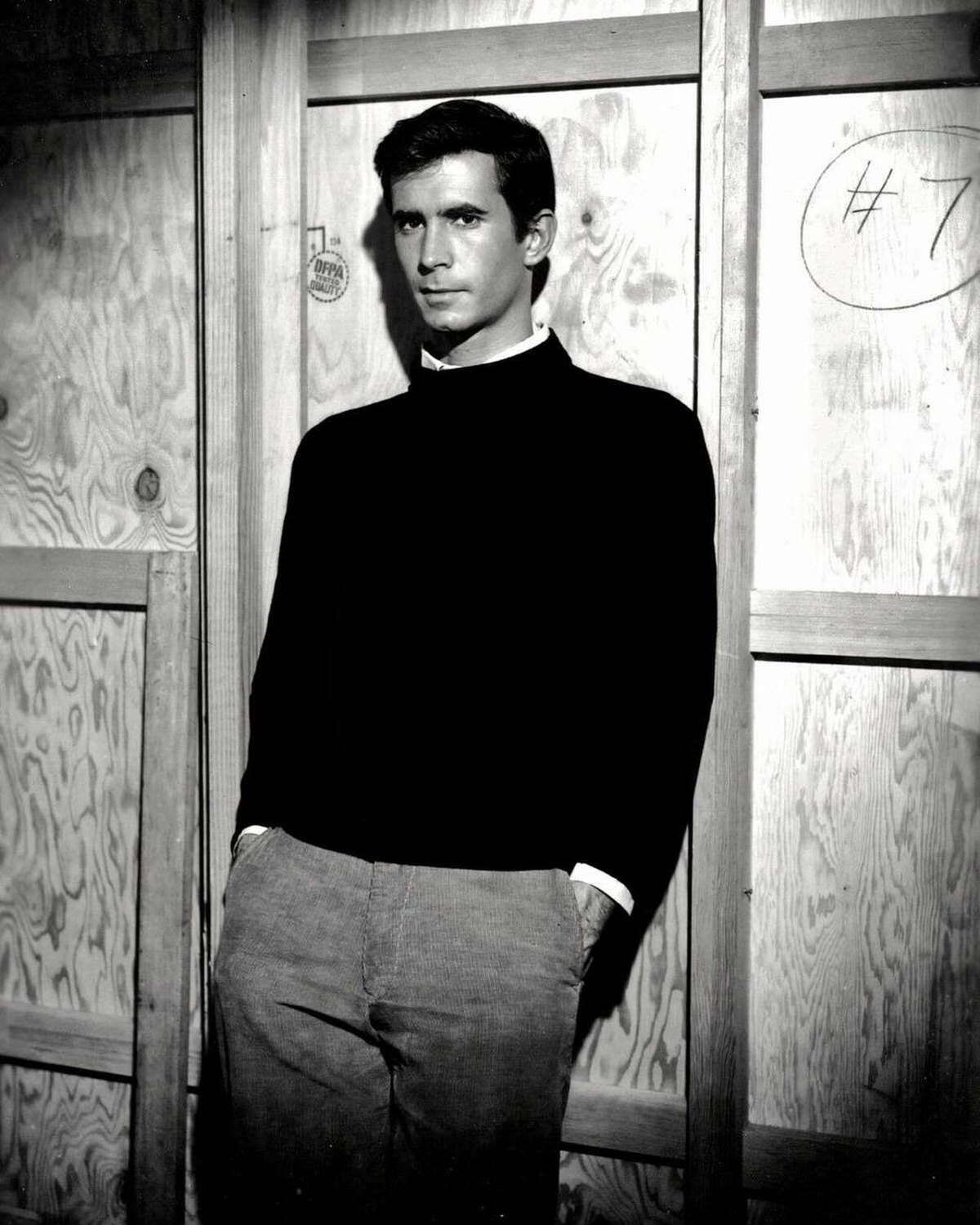

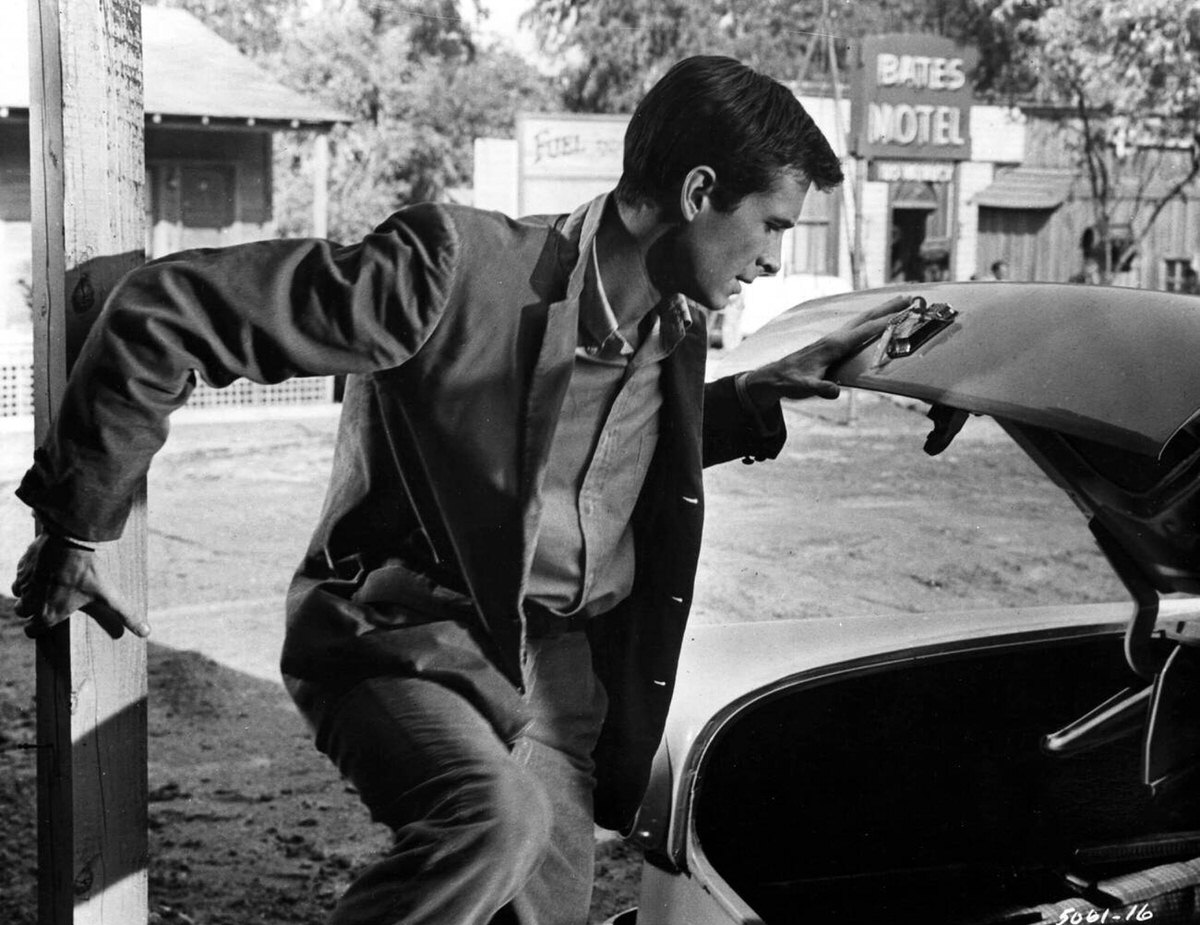

Anthony Perkins was cast as Norman Bates. Perkins brought a quiet, nervous energy to the role. His soft voice and polite manner contrasted with the character’s violent actions. This contrast made Norman more unsettling.

Vera Miles played Lila Crane, Marion’s sister. John Gavin appeared as Sam Loomis, Marion’s lover. Their roles grounded the story after Marion’s death and shifted the film into an investigation.

The Bates Motel and House

The Bates Motel and the house on the hill were built on the Universal Studios lot. The motel was plain and functional, designed to feel forgotten and temporary. The house above it looked old, narrow, and imposing. Its design drew from Gothic architecture, adding a sense of decay and control.

The physical distance between the motel and the house reflected Norman’s divided mind. Hitchcock used this layout to guide camera movement and block scenes with clear purpose.

The Shower Scene

The shower scene became the most famous part of the film. It took seven days to shoot and used over seventy camera setups. The scene relied on fast cuts, close framing, and sharp sound design. The knife never clearly penetrates the body, yet the editing creates the feeling of direct violence.

Chocolate syrup was used as blood because it appeared darker on black-and-white film. Bernard Herrmann’s screeching string score drove the scene’s intensity. Hitchcock first planned to play the scene without music, but Herrmann’s composition changed his mind.

Sound, Editing, and Pacing

Music played a key role throughout the film. Herrmann used only string instruments, which gave the score a tight and anxious tone. The music often replaced dialogue, guiding the audience’s emotional response.

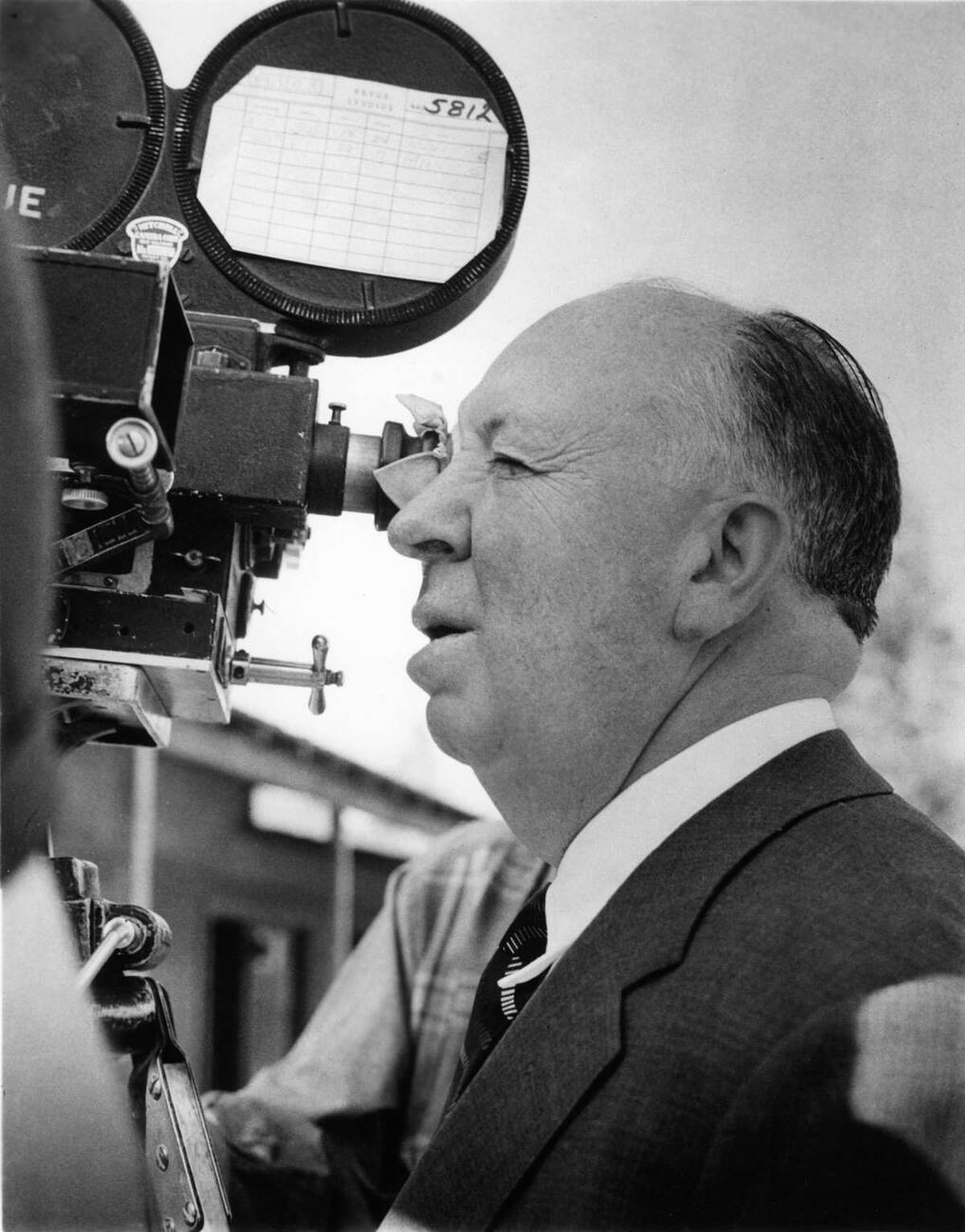

The editing kept scenes short and direct. Hitchcock avoided long explanations and relied on visual clues. Camera placement emphasized isolation, secrecy, and observation. Many shots mimic the feeling of watching someone without their knowledge.

Marketing and Release Strategy

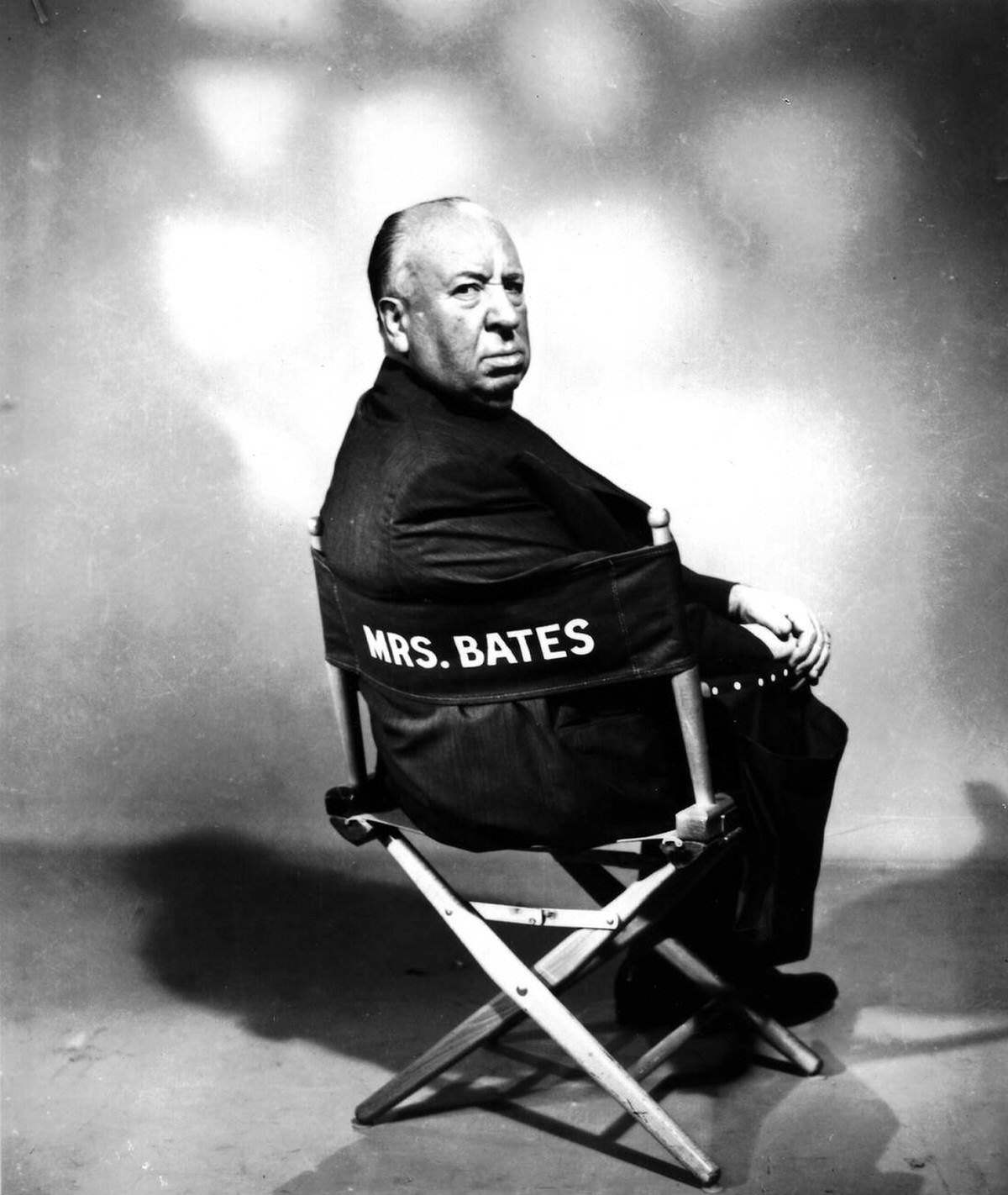

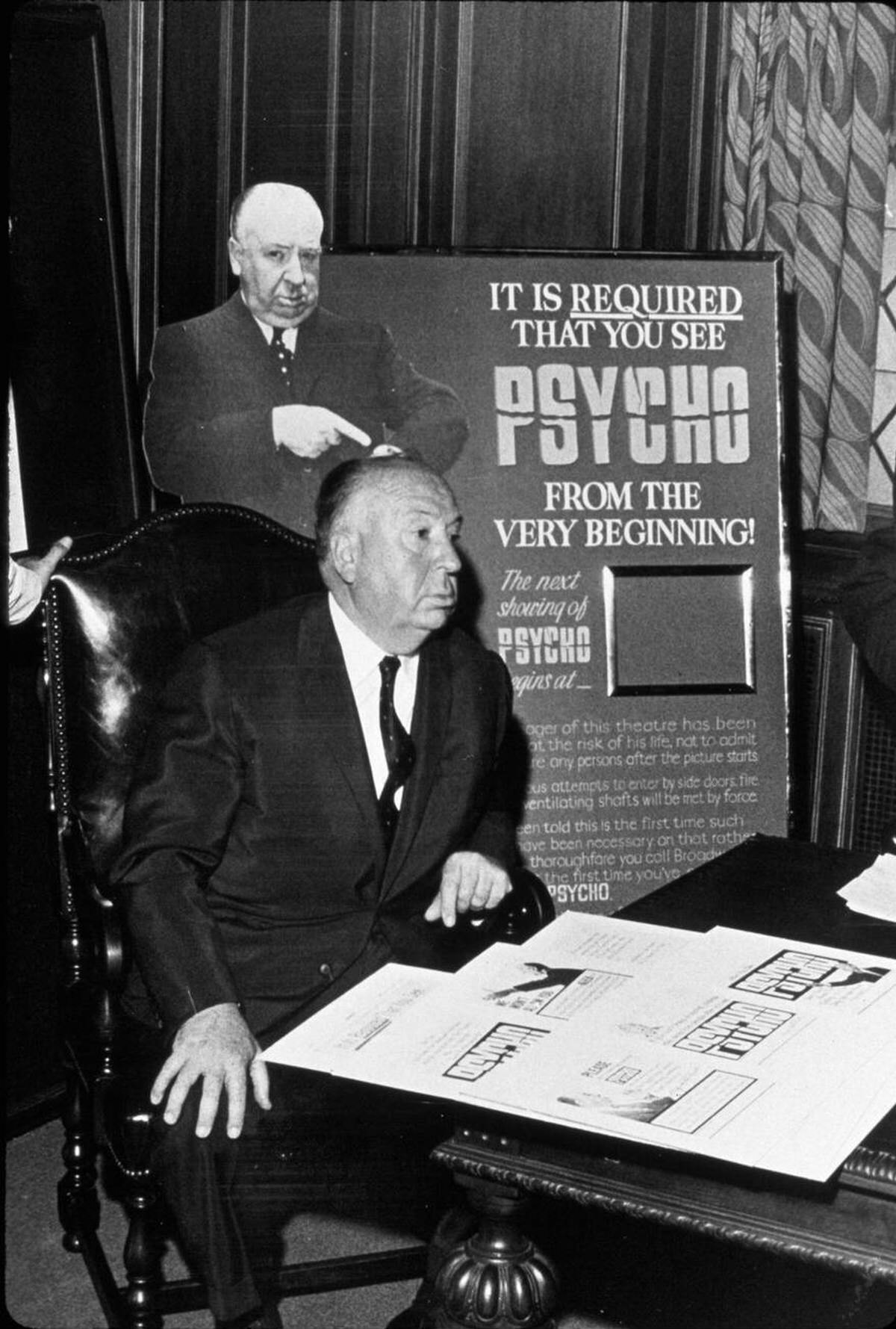

Hitchcock controlled how audiences experienced Psycho. He banned late entry into theaters to protect the story’s surprises. Posters and trailers warned viewers not to reveal the ending. Hitchcock himself appeared in promotional material, framing the film as a shocking experience.

Upon release, critics were divided. Some found the film crude and unsettling. Audiences, however, responded strongly. Long lines formed, and word of mouth spread quickly.

Reevaluation Over Time

Over the years, Psycho gained critical recognition. Scholars and filmmakers studied its structure, themes, and technique. The film is now widely regarded as one of Hitchcock’s most important works. Its production choices, once seen as cheap or risky, are now viewed as deliberate and precise.

The making of Psycho shows Hitchcock working outside the system he helped build. By combining tight control, careful planning, and bold creative decisions, he created a film that still commands attention decades later.